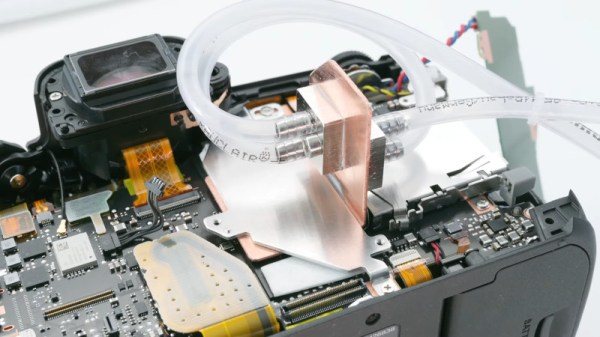

The Canon EOS R5 is a highly capable, and correspondingly very expensive camera. Capable of recording video in 8K in a compact frame size, it unfortunately suffers from frustrating overheating issues. Always one to try an unconventional solution to a common problem, [Matt] decided to whip up a watercooling solution. What ensues is pure, top-notch engineering.

Upon its original release, Canon had the R5 camera simply shut off on a 20 minute timer when recording 8K video. When the userbase complained, an updated firmware was released that used an onboard sensor and would only shutdown when excessive temperatures were reached. Under these conditions, the camera could record for around 25 minutes at 20 °C. [Matt] set about disassembling the camera to investigate, figuring out that the main processor was the primary source of heat. With a poor connection to its heatsink and buried under a power supply PCB, there simply wasn’t anywhere for heat to go, leaving the camera to regularly overheat and take hours to cool down.

After whipping up an amusing but impractical watercooling solution and verifying it allowed the camera to record indefinitely, [Matt] set about some proper thermal engineering. A custom copper heatsink was produced for inside the camera, bonded directly to the processor and DRAM with thermal paste instead of poor-quality thermal tape. This then directs heat out through the plastic back of the camera. In cool environments, this is enough to allow the camera to record continuously. In warmer environments, simply adding a small fan to the back of the camera was enough to keep things operational indefinitely.

[Matt] finishes the video by pointing out that Canon could have made the camera far more useful for videographers by simply investing a little more time into the camera’s cooling design, while also generating more profits by selling a cooling accessory for extended recording. We’ve seen some of [Matt’s] work before too, such as this DIY 4K projector build. Video after the break.

Continue reading “Watercooling A Canon DSLR Leads To Serious Engineering Upgrades”