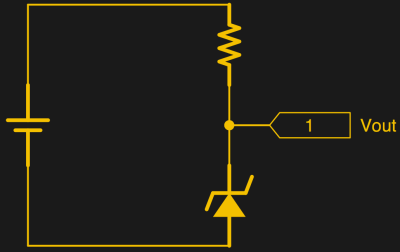

For simple circuits, it’s easy enough to grab a breadboard and start putting it together. Breadboards make it easy to check your circuit for mistakes before soldering together a finished product. But if you have a more complicated circuit, or if you need to do response modeling or other math on your design before you start building, you’ll need circuit simulation software.

While it’s easy to get a trial version of something like OrCAD PSpice, this software doesn’t have all of the features available unless you’re willing to pony up some cash. Luckily, there’s a fully featured free and open source circuit simulation software called Qucs (Quite Universal Circuit Simulator), released under the GPL, that offers a decent alternative to other paid circuit simulators. Qucs runs its own software separate from SPICE since SPICE isn’t licensed for reuse.

Qucs has most of the components that you’ll need for professional-level circuit simulation as well as many different transistor models. For more details, the Qucs Wikipedia page lists all of the features available, as does the project’s FAQ page. If you’re new to the world of circuit simulation, we went over the basics of using SPICE in a recent Hack Chat.

Thanks to [Clovis] for the tip!