There’s nothing more pleasing on a hot day than an ice-cold beverage. While the vast majority of us have a fridge in the kitchen, sometimes it’s desirable to have a further fridge in the lab, games room, or workshop. To that end, you may find value in this ultra-cheap, low-cost DIY fridge build from [Handy_Bear].

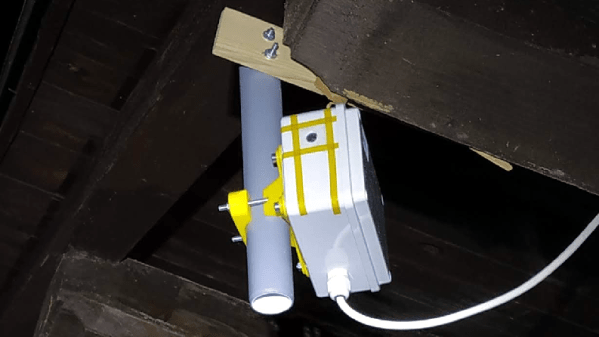

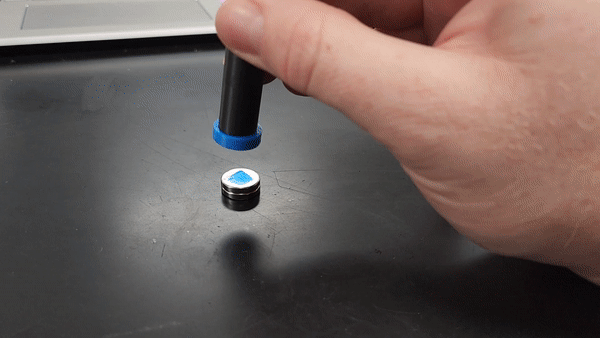

Like many tiny fridge builds, this design eschews complex gas-cycle refrigeration techniques for simple Peltier modules. These are devices that have one cold side and one hot side, because they move heat when electricity is applied. This build uses a Peltier module fitted with a fan to better shift away heat from the hot side, improving the module’s cooling ability.

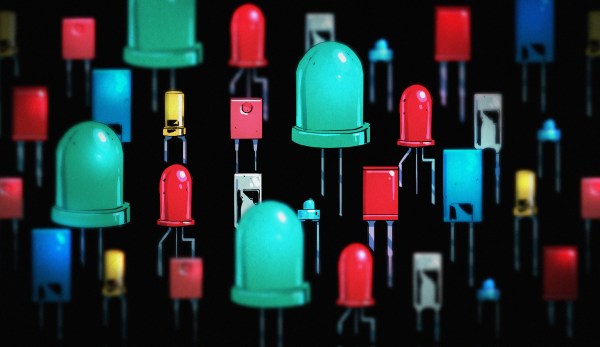

The “fridge” itself is assembled out of thick XPS insulation foam. A hot wire cutter was used to cut several slabs which were then assembled using hot glue. The Peltier module is installed on the back, at the top of the fridge. Thus, air which is cooled in this area will then travel down through the rest of the fridge’s cavity. [Handy_Bear] also goes over how to produce a working hinge and a gasket for the door, which helps with ease-of-use and efficiency. As a nice touch, a set of 12V LED lights are also installed inside, which light when the door is open. Just like the real thing!

The final build is noisy, slow to cool down, and it uses 60 watts of power to cool down just two regulation-sized sodas. Notably, you could fit two standard NATO smoke grenades in the same space, as they’re almost-identically sized (ask us how we know). However, smoke grenades don’t usually need to be refrigerated.

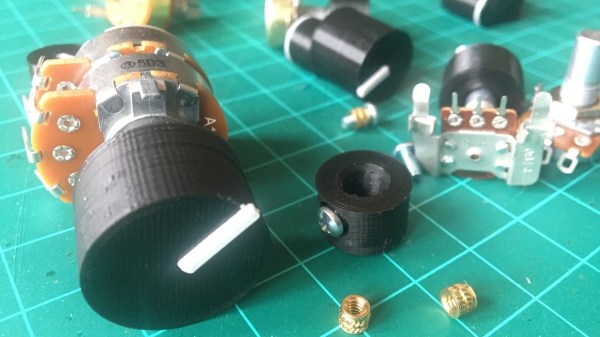

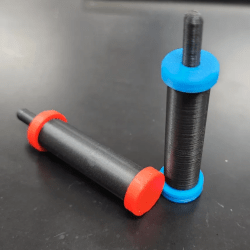

None of that means it isn’t fun though! Plus, [Handy_Bear] notes that adding a second Peltier would greatly aid the fridge’s ability to quickly chill your grenades sodas. You might even like to explore the use of special fan designs to make the fridge even quieter! Video after the break.

Continue reading “DIY Mini Fridge Is Pure Brilliance In Foam”