Data exfiltration via side channel attacks can be a fascinating topic. It is easy to forget that there are so many different ways that electronic devices affect the physical world other than their intended purpose. And creative security researchers like to play around with these side-effects for ‘fun and profit’.

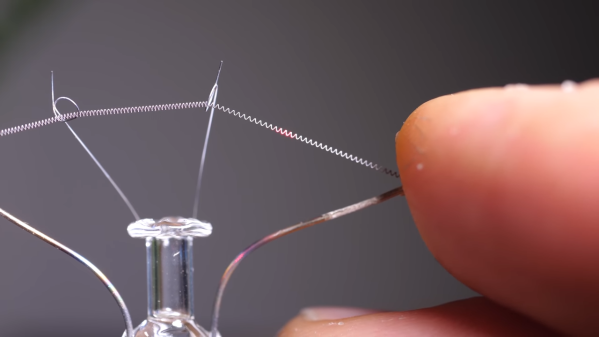

Engineers at the University of California have devised a way to analyse exactly what a DNA synthesizer is doing by recording the sound that the machine makes with a relatively low-budget microphone, such as the one on a smart phone. The recorded sound is then processed using algorithms trained to discern the different noises that a particular machine makes and translates the audio into the combination of DNA building blocks the synthesizer is generating.

Although they focused on a particular brand of DNA Synthesizers, in which the acoustics allowed them to spy on the building process, others might be vulnerable also.

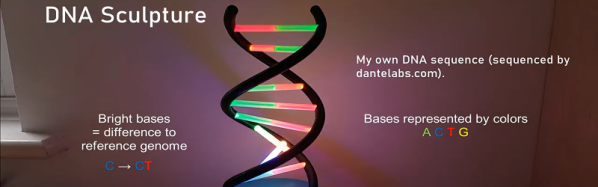

In the case of the DNA synthesizer, acoustics revealed everything. Noises made by the machine differed depending on which DNA building block—the nucleotides Adenine (A), Guanine (G), Cytosine (C), or Thymine (T)—it was synthesizing. That made it easy for algorithms trained on that machine’s sound signatures to identify which nucleotides were being printed and in what order.

Acoustic snooping is not something new, several interesting techniques have been shown in the past that raise, arguably, more serious security concerns. Back in 2004, a neural network was used to analyse the sound produced by computer keyboards and keypads used on telephones and automated teller machines (ATMs) to recognize the keys being pressed.

You don’t have to rush and sound proof your DIY DNA Synthesizer room just yet as there are probably more practical ways to steal the genome of your alien-cat hybrid, but for multi-million dollar biotech companies with a equally well funded adversaries and a healthy paranoia about industrial espionage, this is an ear-opener.

We written about other data exfiltration methods and side channels and this one, realistic scenario or not, it’s another cool audio snooping proof of concept.