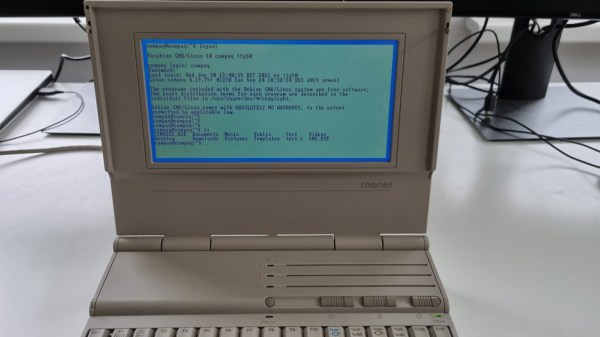

We love retrocomputing and tiny computers here at Hackaday, so it’s always nice to see projects that combine the two. [Eivind]’s TinyLlama lets you play DOS games on a board that fits in your hand.

Using the 486 SOM from the 86Duino, the TinyLlama adds an integrated Crystal Semiconductor audio chip for AdLib and SoundBlaster support. If you populate the 40 PIN Raspberry Pi connector, you can also use a Pi Zero 2 to give the system MIDI capabilities when coupled with a GY-PCM5102 I²S DAC module.

Audio has been one of the trickier things to get running on these small 486s, so its nice to see a simple, integrated solution available. [Eivind] shows the machine running DOOM (in the video below the break) and starts up Monkey Island at the end. There is a breakout board for serial and PS/2 mouse/keyboard, but he says that USB peripherals work well if you don’t want to drag your Model M out of the closet.

Looking for more projects using the 86Duino? Checkout ISA Sound Cards on 86Duino or Using an 86Duino with a Graphics Card.