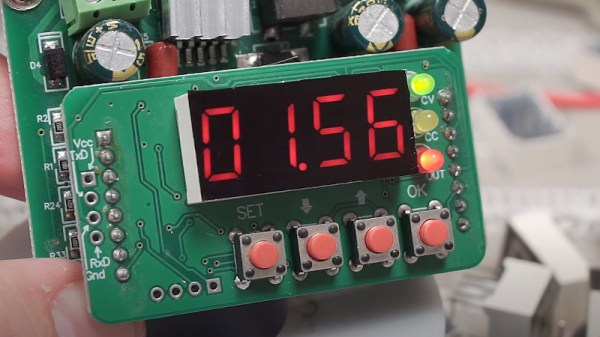

We’re suckers for a nice seven-segment LED display around these parts, and judging by how often they seem to pop up in the projects that come our way, it seems the community is rather fond of them as well. But though they’re cheap, easy to work with, and give off that all important retro vibe, they certainly aren’t perfect. For one thing, their visibility can be pretty poor in some lighting conditions, especially if you’re trying to photograph them for documentation purposes.

If this is a problem you’ve run into recently, [Hugatry] has a simple tip that might save you some aggravation. With a scrap piece of automotive window tint material, it’s easy to cut a custom filter that you can apply directly to the face of the display. As seen in the video, the improvement is quite dramatic. The digits were barely visible before, but with the added contrast provided by the tint, they stand bright and beautiful against the newly darkened background.

[Hugatry] used 5% tint film for this demonstration since it was what he already had on hand, but you might want to experiment with different values depending on the ambient light levels where you’re most likely to be reading the display. The stuff is certainly cheap enough to play around with — a quick check seems to show that for $10 USD you can get enough film to cover a few hundred displays. Which, depending on the project, isn’t nearly as overkill as you might think.

Continue reading “Quick Tip Improves Seven-Segment LED Visibility”