Gravity can be a difficult thing to simulate effectively on a traditional CPU. The amount of calculation required increases exponentially with the number of particles in the simulation. This is an application perfect for parallel processing.

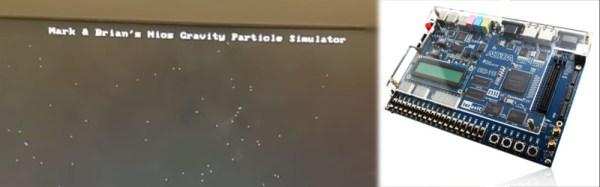

For their final project in ECE5760 at Cornell, [Mark Eiding] and [Brian Curless] decided to use an FPGA to rapidly process gravitational calculations. This allows them to simulate a thousand particles at up to 10 frames per second. With every particle having an attraction to every other, this works out to an astonishing 1 million inverse-square calculations per frame!

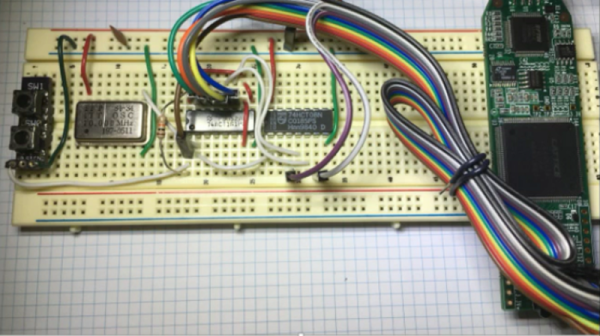

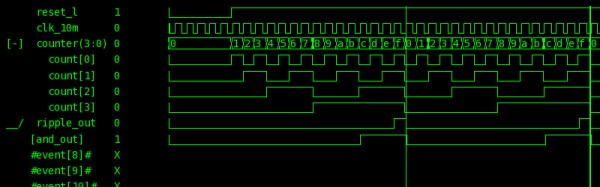

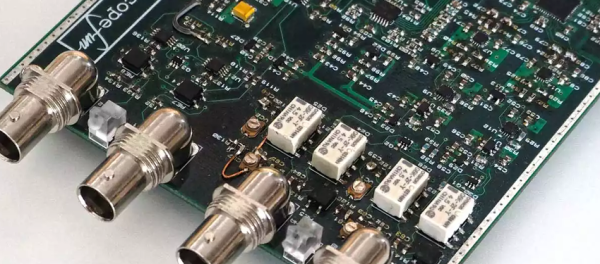

The team used an Altera DE2-115 development board to build the project. General operation is run by a Nios II processor, which handles the VGA display, loads initial conditions and controls memory. The FPGA is used as an accelerator for the gravity calculations, and lends the additional benefit of requiring less memory access operations as it runs all operations in parallel.

This project is a great example of how FPGAs can be used to create serious processing muscle for massively parallel tasks. Check out this great article on sorting with FPGAs that delves deeper into the subject. Video after the break.