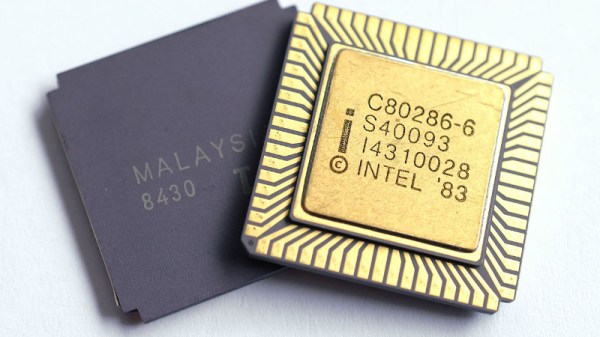

Though it is largely forgotten today, the Intel 80286 was for a while in the 1980s the processor of choice and designated successor to the 8086 in the world of PCs. It brought a new mode that could address up to 16 Mb of memory, and a welcome speed boost over machines using an 8086 or 8088. As with many microprocessors, it has a few undocumented features, and it’s a couple of these that [rep lodsb] takes a look at. Along the way we learn a bit about the 286, and about why Intel had some of these undocumented instructions in the first place.

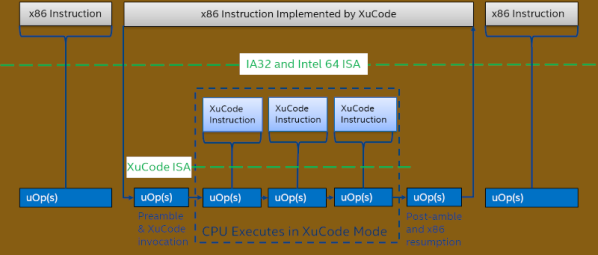

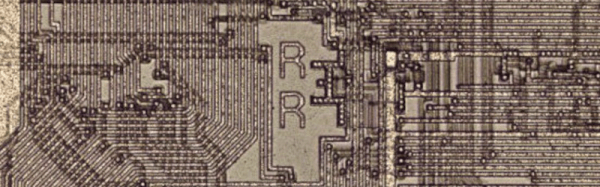

If you used a 286 it was probably as an end-user sitting in front of a PC-AT or clone. During manufacture and testing though, the processor had need of some extra functions, both for testing the chip itself and for debugging designs using it. It’s in these fields that the undocumented instructions sit, and they relate to an in-circuit emulator, a 286 with a debug port on some of its unused pins, which would have sat on a plug-in daughterboard for systems under test. The 286 was famous for its fancy extended mode taking rather a long time to switch to, and these instructions relate to loading and saving states before and after the switch.

The 286s time as the new hotness was soon blasted away by the 386 with its support for virtual memory, so for most of us it remains as simply a faster way that we ran 8086 code for a few years. They appear from time to time here, even being connected to the internet.

286 image: Thomas Nguyen (PttNguyen.net), CC BY-SA 4.0.