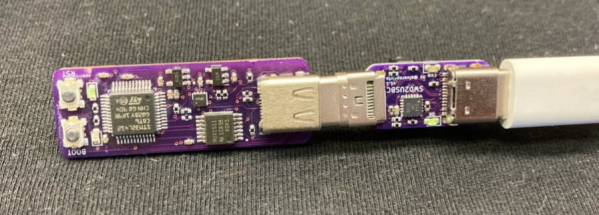

[Thomas Roth], aka [Ghidraninja], and author of the [Stacksmashing] YouTube channel, investigated Apple’s Lightning port and created a cool debugging tool that allowed one to get JTAG on the device. Then, Apple went to USB-C for their new phones, and all his work went to waste. Oh well, start again — and take a look at USB-C.

Turns out, though, that the iPhone 15 uses the vendor-defined messages (VDM) capability of USB-PD to get all sorts of fun features out. Others had explored the VDM capabilities on Mac notebooks, and it turns out that the VDM messages on the phone are the same. Some more fiddling, and he got a serial port and JTAG up and running. But JTAG is locked down in the production devices, so that will have to wait for an iPhone 15 jailbreak. So he went poking around elsewhere.

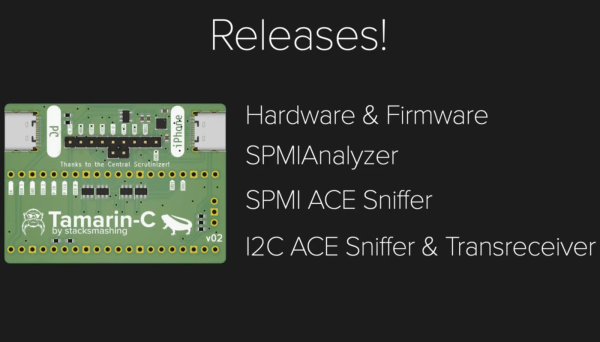

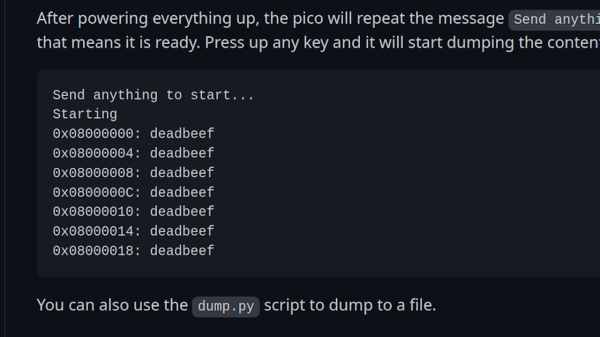

He found some other funny signals that turned out to be System Power Management Interface (SPMI), one of the horribly closed and NDA-documented dialects owned by the MIPI Alliance. Digging around on the Interwebs, he found enough documentation to build an open-source SPMI plugin that he said should be out on his GitHub soon.

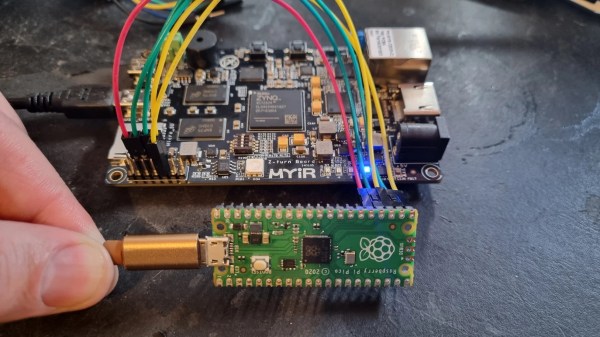

The end result? He reworked his old Lightning hardware tool for USB-C and poked around enough in the various available protocols to get a foothold on serial, JTAG, and SPMI. This is just the beginning, but if you’re interested in playing with the new iPhone, this talk is a great place to start. Want to know all about USB-C? We’ve got plenty of reading for you.