Harvesting energy from the human body may sound scary, but fortunately a Matrix-style setup exists only as a cinematic fiction. Instead a typical path lies in external contraptions that use the body’s natural motions to drive a small generator, a bit of flexible piezo material, and so on. A popular target for harvesting the body’s kinetic energy is the knee joint, as this has a comparatively large range of motion and is fairly easy to use.

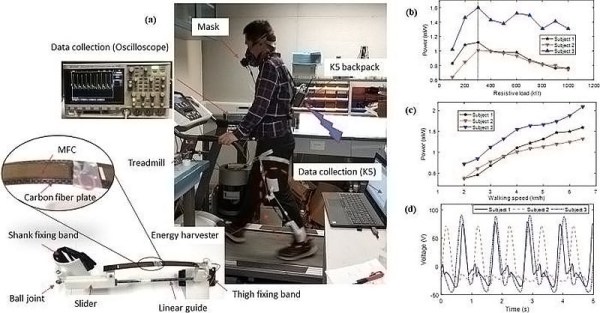

Thus a team from Hong Kong university opted to pick this part of the human anatomy for their experiment as well. While at first glance their results do not seem particularly impressive, with up to 1.6 mW of power generated, a look at their published results in the Applied Physics Letters journal showed their reasoning behind this setup. While one generator-based setup referenced produces on average 4.8 Watt of power, the device itself weighs 1.6 kg and increases the rate at which the person wearing it burns calories by a significant amount.

The goal for this device was to have a way to generate significant amounts of power without having the user exerting themselves more than usual. This led to them using flexible piezoelectric composites, resulting in a weight of just 307 grams, based upon two M8514-P2 pieces (Smart Materials Corp. manufacturer). Tests with volunteers on a treadmill show that users do not burn more calories than without.

As with all piezo materials, they can flex a bit, but not too much, so a lot of time and effort went into calculating the optimal bend radius in different usage scenarios. While around 1 mW of power is not massive, it is a reliable source of power for individuals who do any amount of walking during the day and doesn’t require any effort beyond strapping the device onto one’s legs.