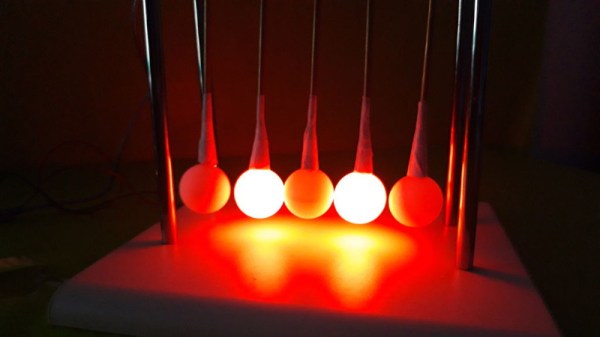

Newton’s Cradle was once upon a time, a popular desk toy in offices around the world. For [TecnoProfesor], however, it wasn’t quite flashy enough. Instead, they built a simulated version with flashing LEDs. As you do.

Rather than relying on the basic principles of the cradle to make it work, this relies on two servo motors to move the balls on the ends, with the ones in the middle remaining stationary. Each ball is fitted with an RGB LED, which flashes with the simulated “motion” of the cradle. By using ping pong balls, the light from the LEDs is nicely diffused. The frame is built from wooden dowels, metal rods, and acrylic.

It’s a project that is sure to confuse at first glance, but it’s a great way to learn basic microcontroller skills like interfacing with LEDs and servomotors. We’d love to see a version that works like a real Newton’s Cradle, flashing the LEDs as they are hit by their neighbours. We’ve even seen them automated, for the truly lazy among us. Alternatively, one could go completely ridiculous and have such a device tweet on every hit, though you might run afoul of the API’s spam restrictions. If you give it a go, drop us a line.