As any musician, podcaster, or youtuber will be quick to tell you, there’s no substitute for a good microphone. They’ll also be quick to tell you all about their favorite microphone, why it’s better than all the others, and how much it cost (oh, and how round it sounds, whatever that means). But what if you could build your own that sounds as good, if not better, and do it for only $30?

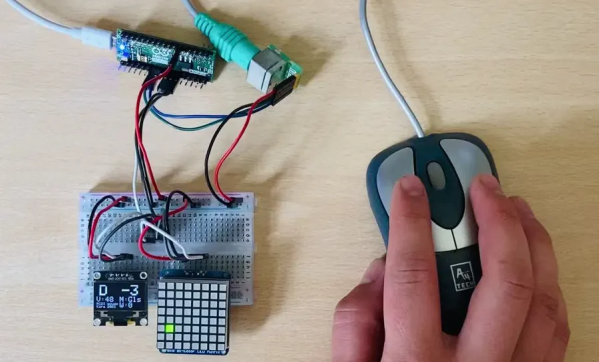

That’s what [Matt] from DIY Perks set out to discover when he built his DIY USB-C Microphone. He was able to source the same microphone capsule that can be found in his high-end, $600 CAD E100S, and built a simple pre-amplifier that bumps its quiet output up to line-level. He even connected it to the mic module with some custom cable made from two tiny enameled wires that won’t transmit bumps and vibrations, wrapped inside desoldering braiding which acts as a shield. He fed the output from the pre-amp into a cheap USB audio interface and voilà! — top-notch sound for next to nothing. Make sure you check out the video below to hear a comparison between the mic and its professional counterparts.

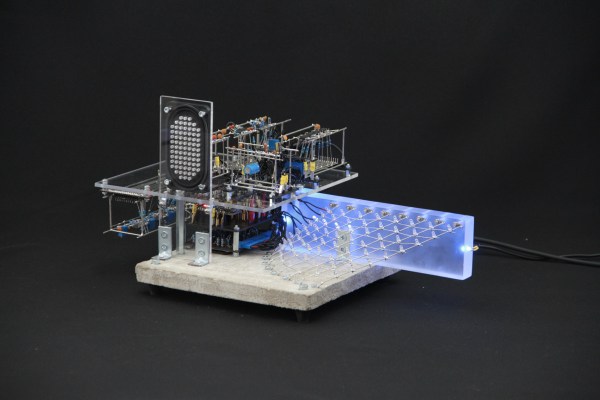

Of course, sounding good isn’t quite enough. [Matt] wasn’t satisfied until the piece looked the part as well, which is why he encased the mic module in custom-bent brass mesh shielding and tubing (which also helps to reduce electrical interference). The brass cage sits suspended via rubber o-rings on a beautiful bent brass mount, which sits atop an articulated brass arm of [Matt]’s own design. Finally, the arm is mounted to a wood and brass enclosure that also serves to house the electronics.

And, in true open-source fashion, the video description is full of links to parts, schematics, and templates in case you want to build one of these beauties for yourself. Between this fantastic build and this other, super-overkill scratch-built USB microphone we featured earlier in the year, there has never been a better time to make yourself a mic you won’t have to trade your car for.

Thanks to [RichV] and [BaldPower] for the tip!

Continue reading “Cheap DIY Mic Sounds (And Looks) Damn Good”