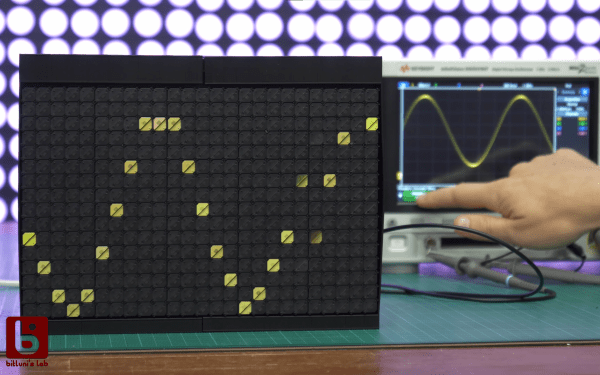

Oscilloscope displays have come a long way since the round phosphor-coated CRTs that adorned laboratories of old. Most modern scopes ship with huge, high-definition touch screens that, while beautiful, certainly lack a bit of the character that classic scopes brought to the bench. It’s a good thing that hackers like [bitluni] are around to help remedy this. His contribution takes the form of what may be both the world’s coolest and least useful oscilloscope: one with a flip-dot display.

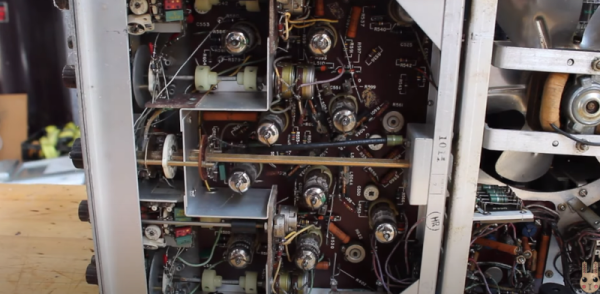

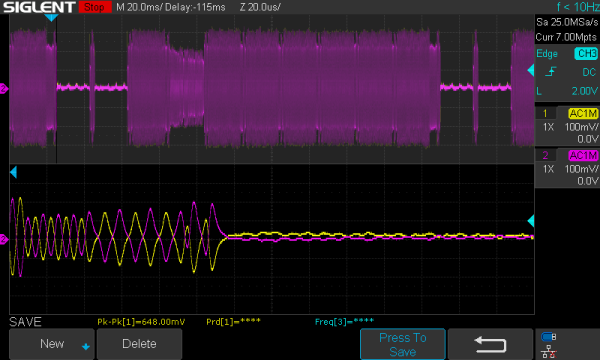

Yup — a flip-dot display, in all it’s clickedy-clacky, 25×16 pixel glory. The scope can’t trigger, its maximum amplitude is only a couple of volts, and its refresh rate is, well, visible, but it looks incredible. The scope is controlled by an ESP32, which reads the analog signal being measured. It then displays the signal via an array of driver ICs, which allow it to update the dots one column at a time by powering the tiny electromagnets that flip over each colored panel.

Even better, [bitluni] live-streamed the entire build. That’s right, if you want to watch approximately 30 hours of video covering everything from first actuating a pixel on the display to designing and assembling a PCB to drive it, then you’re in luck. For the rest of us, he was kind enough to make a much shorter summary video you can watch below. Of course, this scope doesn’t run Doom like some others, but its probably only a matter of time.

Thank to [Zane Atkins] for the tip!

Continue reading “Flip-Dot Oscilloscope Is Flippin’ Awesome”