[Justin] from The Thought Emporium takes on a common molecular biology problem with these homebrew heating instruments for the DIY biology lab.

The action at the molecular biology bench boils down to a few simple tasks: suck stuff, spit stuff, cool stuff, and heat stuff. Pipettes take care of the sucking and spitting, while ice buckets and refrigerators do the cooling. The heating, however, can be problematic; vessels of various sizes need to be accommodated at different, carefully controlled temperatures. It’s not uncommon to see dozens of different incubators, heat blocks, heat plates, and even walk-in environmental chambers in the typical lab, all acquired and maintained at great cost. It’s enough to discourage any would-be biohacker from starting a lab.

[Justin] knew It doesn’t need to be that way, though. So he tackled two common devices: the incubator and the heating block. The build used as many off-the-shelf components as possible, keeping costs down. The incubator is dead simple: an insulated plastic picnic cooler with a thermostatically controlled reptile heating pad. That proves to be more than serviceable up to 40°, at the high end of what most yeast and bacterial cultures require.

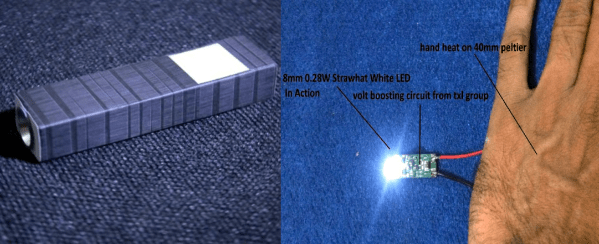

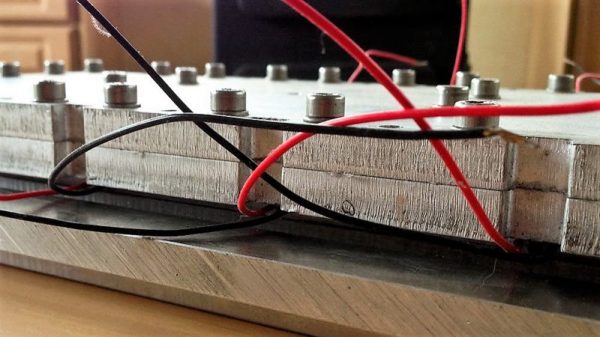

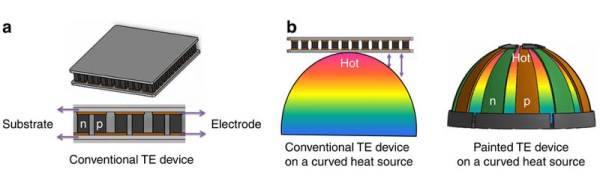

The heat block, used to heat small plastic reaction vessels called Eppendorf tubes, was a little more complicated to construct. Scrap heat sinks yielded aluminum stock, which despite going through a bit of a machinist’s nightmare on the drill press came out surprisingly nice. Heat for the block is provided by a commercial Peltier module and controller; it looks good up to 42°, a common temperature for heat-shocking yeast and tricking them into taking up foreign DNA.

We’re impressed with how cheaply [Justin] was able to throw together these instruments, and we’re looking forward to seeing how he utilizes them. He’s already biohacked himself, so seeing what happens to yeast and bacteria in his DIY lab should be interesting.

Continue reading “Hacked Heating Instruments For The DIY Biology Lab”