Telepresence hasn’t taken off in a big way just yet; it may take some time for society to adjust to robotic simulacra standing in for humans in face-to-face communications. Regardless, it’s an area of continuous development, and [MakerMan] has weighed in with a tidy DIY build that does the job.

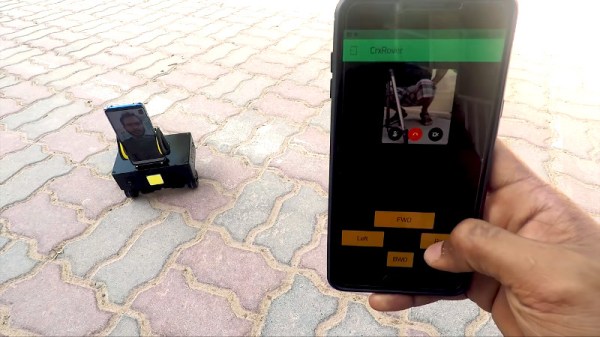

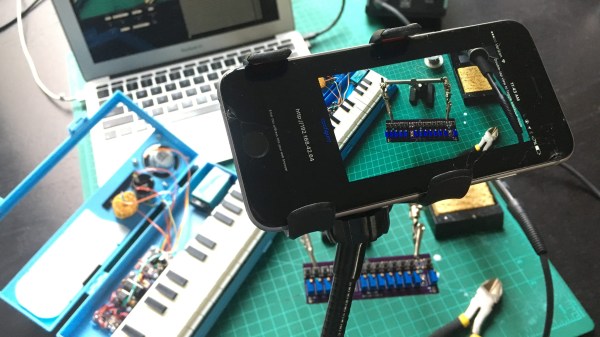

It’s a build that relies on an assemblage of off-the-shelf parts to quickly put together a telepresence robot. Real-time video and audio communications are easily handled by a Huawei smartphone running Skype, set up to automatically answer video calls at all times. The phone is placed onto the robotic chassis using a car cell phone holder, attached to the body with a suction cup. The drive is a typical two-motor skid steer system with rear caster, controlled by a microcontroller connected to the phone.

Operation is simple. The user runs a custom app on a remote phone, which handles video calling of the robot’s phone, and provides touchscreen controls for movement. While the robot is a swift mover, it’s really only sized for tabletop operation — unless you wish to talk to your contact’s feet. However, we can imagine there has to be some charm in driving a pint-sized ‘bot up and down the conference table when Sales and Marketing need to be whipped back into shape.

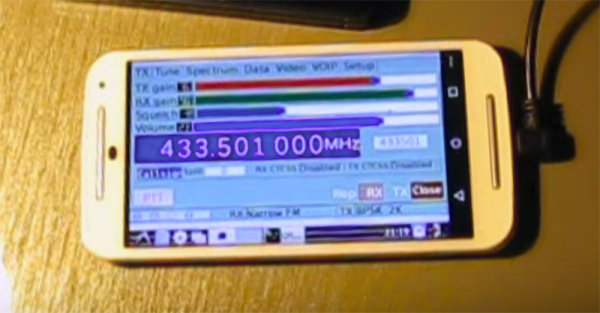

It’s a build that shows that not everything has to be a 12-month process of research and development and integration. Sometimes, you can hit all the right notes by cleverly lacing together a few of the right eBay modules. Getting remote video right can be hard, too – as we’ve seen before.