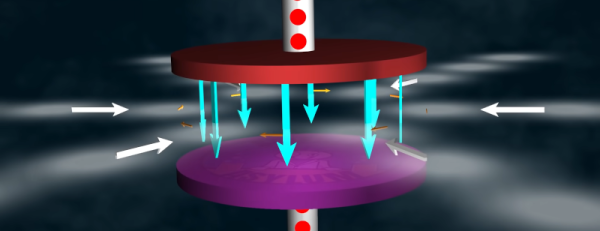

About a year ago, [Wyman’s Workshop] needed a fan. But not just a regular-old fan, no sir. A ducted fan. You know, those fancy fan designs where the stationary shroud is so close to the moving fan blades that there’s essentially no gap, and a huge gain in aerodynamic efficiency? At least in theory?

Well, in practice, you can watch how it turned out in this video. (Also embedded below.) If you’re more of a “how-to-build-it” type, you’ll want to check out his build video — there’s lots of gluing 3D prints and woodworking. But we’re just in it for the ducted fan data!

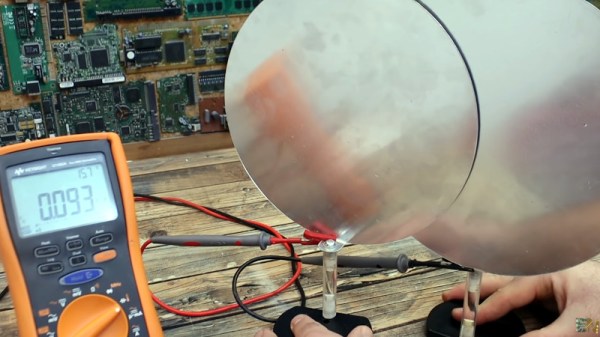

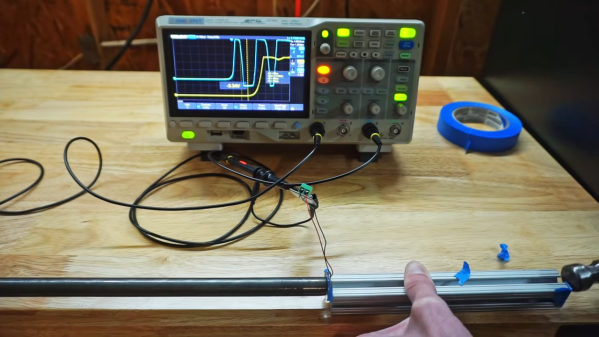

And that’s why we’re writing it up! [Wyman] made a nice thrust-testing rig that the fan can pull on to figure out how much force it put out. And the theory aimed at 652 g of thrust, which was roughly confirmed. And then you get to power: with a 500 watt motor, he ended up producing 47 watts. Spoiler: he’s overloading the motor, even though he used a fairly beefy bench grinder motor.

So he re-did the fan design, from scratch, to better match the motor. And it performed better than the theory said it would. A pleasant surprise, but it meant re-doing the theory, including the full volume of the fan blade, which finally brought theory and practice together. Which then lead him design a whole slew of fan blades and test them out against each other.

He ends the video with a teaser that he’ll show us the results from various inlet profiles and fan cones and such. But the video is a year old, so we’re not holding our breath. Still, if you’re at all interested in fan design, and aren’t afraid of high-school physics, it’s worth your time.

Don’t care about the advantages of ducted fans, but simply want to make your quad look totally awesome? Have we got the hack for you!