When thinking of the first PCs, most of us might imagine something like the Apple I or the TRS-80. But even before that, there were a set of computers that often had no keyboard, or recognizable display beyond a few blinking lights. [Artem Kalinchuk] is attempting to recreate one of these very early digital computers, the Kenbak-1, using as many period-correct parts as possible.

Considered by many to be the world’s first personal computer, the Kenbak-1 was an 8-bit machine with 256 bytes of memory, using TTL integrated circuits for the logic as there was no commercially available microprocessor available at the time it was designed. For [Artem]’s build, most of these parts can still be sourced including the 7400-series chips and carbon resistors although the shift registers were a bit of a challenge to find. A custom PCB was built to replicate the original, and with all the parts in order it’s ready to be assembled and put into a case which was built using the drawings for the original unit.

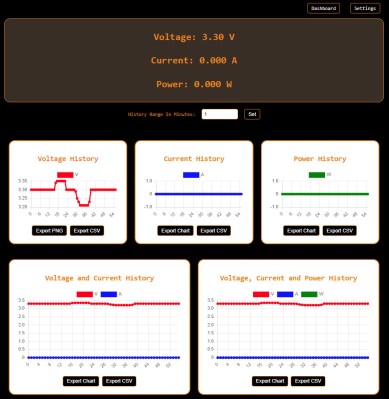

Although [Artem] plans to build a period-correct linear power supply for this computer, right now he’s using a modern switching power supply for testing. The only other major components that are different are the status lamps, in this case switched to LEDs because he wasn’t able to source incandescent bulbs that drew low enough current, and the switches which he’s replaced with MX-style keys. We’ll stay tuned as he builds and tests this over the course of several videos, but in the meantime if you’re curious how this early computer actually worked we featured an emulator for it a while back.

Continue reading “Rebuilding The First Digital Personal Computer”