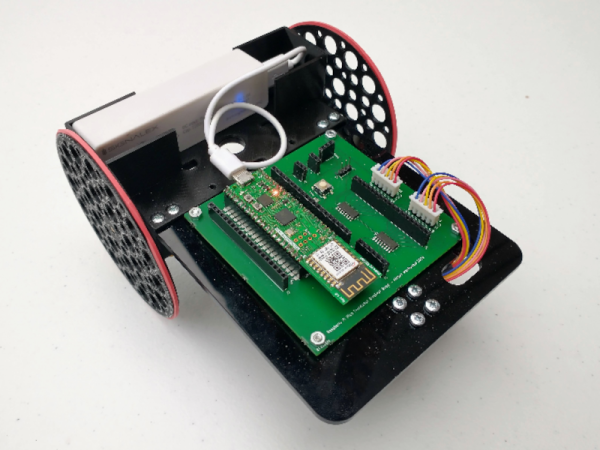

We’ve seen a lot of weather displays over the years, and plenty of the more modern ones have been using some form of electronic paper. So what makes this particular build from [Harry Stern] different? The fact that the firmware running on the ESP32 microcontroller at its heart was developed in Rust.

The weather station itself is capable of operating for several months on its rechargeable NiMH battery bank. The Rust section of the project is in two parts, the first of which runs on a server which downloads the weather data and aggregates it into an image. The second part runs on the ESP32 using esp-idf which configures peripherals, turns on and connects to Wi-Fi, retrieves the image from the server, displays the image and then puts the display to sleep. By doing the heavy lifting on the server, the display should be able to run for longer than it would if everything was happening on the ESP32.

The project code is available from this GitHub page which should allow even Rust beginners to follow along, and the case file is also available for those with a 3D printer. [Harry] has a few upgrades planned for future releases as well, including a snap-fit case, a custom PCB, and improved voltage regulator for better battery life, and enhanced error handling for the weather API. And Rust isn’t the only interesting part of this project, either. As prices for e-paper displays continue to fall, more and more of them are found in projects like weather stations and even complete laptops which use these displays exclusively.