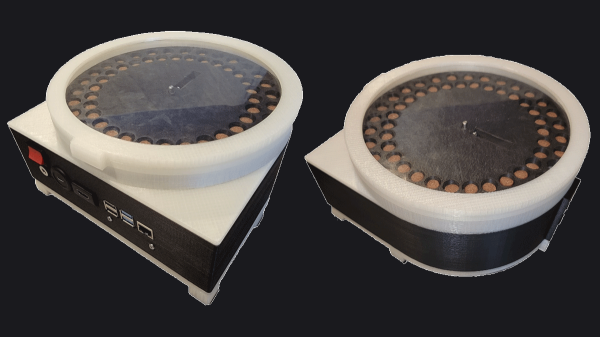

Fire up those 3D printers because if you’re like us, you’ll want your own PlottyBot. Still, have a pile of “thank you notes” to write from recent winter holiday gift exchanges? Hoping to hand letter invitations to a wedding or other significant event? Need some new art to adorn your lock-down shelter or shop? It sounds like [Ben] could help you with that.

Besides being a handsomely designed desktop DrawBot, this project from [Ben] looks to have some solid software to run it, a community of makers who have tested the waters, and very detailed build instructions. Those include everything from a BOM with links for ordering parts to animated GIF assembly for the trickier steps.

If you’d like to graduate from “handwritten” cards and letters to something poster-sized are customization tips for expanded X and Y dimensions. As we’ve included in other recent articles, one caveat to mention is the current scarcity of the Raspberry Pi Zeros that PlottyBots require. But if you have one on hand or think you’ll be able to source one by the time you’ve 3D printed all the parts, it might just be the perfect time to add another bot to your family. As a heads up, this project is self-hosted on a solar-powered server, so maybe take turns reading the complete build log.

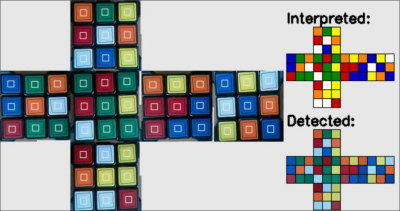

A nice bonus if you need help drawing something suitably complex to require a robot’s help, [Ben] also created MandalGaba which looks like an awesome online tool for drawings like the ones shown above.