When it comes to lithium batteries, you basically have two types. LiPoly batteries usually come in pouches wrapped in heat shrink, whereas lithium ion cells are best represented by the ubiquitous cylindrical 18650 cells. Are there exceptions? Yes. Is that nomenclature technically correct? No, LiPoly cells are technically, ‘lithium ion polymer cells’, but we’ll just ignore the ‘ion’ in that name for now.

Lithium ion cells are found in millions of ground-based modes of transportation, and LiPoly cells are the standard for drones and RC aircraft. [Tom Stanton] wondered why that was, so he decided to test the energy density per mass of these battery chemistries, and what he found was very interesting.

The goal of [Tom]’s experiment was to test LiPoly against lithium ion batteries in the context of a remote-controlled aircraft. Since weight is what determines flight time, cutting even a few grams from an airframe can vastly extend the capabilities of an aircraft. The test articles for this experiment come in the form of a standard 1800 mAh LiPoly battery and four 18650 cells wired together as a 3000 mAh battery. Here’s where things get interesting: the LiPoly battery weighs 216 grams for an energy density of 0.14 Watt-hours per gram. The lithium ion battery weighs 202 grams for an energy density of 0.25 Watt-hours per gram. If you just look at the math, all drones are doing it wrong. 18650 cells appear to have a much higher energy density per mass than the usual LiPoly cells. How does that hold up in a real-world test, though?

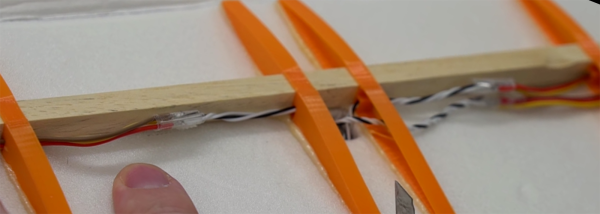

Using his neat plane with 3D printed wing ribs as the testbed, [Tom] plugged in the batteries and flew around a field for the better part of an afternoon. The LiPo flew for 41.5 minutes, whereas the much more energy dense lithium ion battery flew for 36.5 minutes. What’s going on here?

While the lithium ion battery has a much higher capacity, the problem here is the internal resistance of each battery chemistry. The end voltage for the LiPo was a bit lower than the lithium ion battery, suggesting the 18650 cells can be run down a bit further than [Tom]’s test protocol allowed. After recharging each of these batteries and doing a bit of math, [Tom] found the lithium ion batteries can fly for about twice as long as their LiPo counterparts. That means an incredibly long test of flying a plane in a circle over a field; not fun, but we are looking forward to other people replicating this experiment.

Continue reading “Lithium Ion Versus LiPoly In An Aeronautical Context”