In today’s value-engineered world, getting a decade of service out of a cordless tool is pretty impressive. By that point you’ve probably gotten your original investment back, and if the tool gives up the ghost, well, that’s what the e-waste bin is for. Not everyone likes to give up so easily, though, which results in clever repairs like the one that brought this cordless driver back to life.

The Black & Decker “Gyrodriver,” an interesting tool that is controlled with a twist of the wrist rather than the push of a button, worked well for [Petteri Aimonen] right up until the main planetary gear train started slipping thanks to stripped teeth on the plastic ring gear. Careful measurements of one of the planetary gears to determine parameters like the pitch and pressure angle of the teeth, along with the tooth count on both the planet gear and the stripped ring.

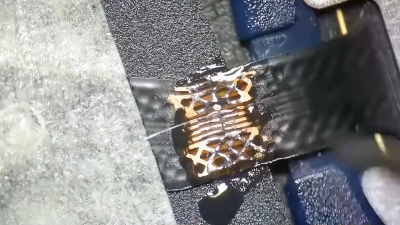

Here, most of us would have just 3D printed a replacement ring gear, but [Petteri] went a different way. He mentally rolled the ring gear out, envisioning it as a rack gear. To fabricate it, he simply ran a 60° V-bit across a sheet of steel plate, creating 56 parallel grooves with the correct pitch. Wrapping the grooved sheet around a round form created the ring gear while simultaneously closing the angle between teeth enough to match the measured 55° tooth angle in the original. [Petteri] says he soldered the two ends together to form the ring; it looks more like a weld in the photos, but whatever it was, the driver worked well after the old plastic teeth were milled out and the new ring gear was glued in place.

We think this is a really clever way to make gears, which seems like it would work well for both internal and external teeth. There are other ways to do it, of course, but this is one tip we’ll file away for a rainy day.