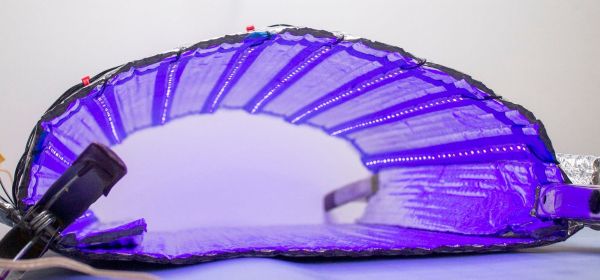

Ultraviolet (UV) curing lamps are crucial if you have a resin 3D printer or work with UV adhesives. Some folks line an old Amazon shipping box with foil and drop a spotlight somewhere inside. Other folks toss their work under the all-natural light source, Sol. Both options have portability and reliability problems, but [AudreyObscura] has it covered with a reflective mat lined with UV strip lights. This HackadayPrize2020 finalist exemplifies the ideal that good ideas are often simple, and this has a remarkably short bill of materials.

Foil bubble insulation is the medium because it provides structure and reflectivity, but it doesn’t cooperate with the LED strip’s adhesive. [AudreyObscura] demonstrates that masking tape as an interfacing layer makes everyone play nicely. A fine example of an experienced maker, their design covers bundling wires and insulating connections to keep everything tidy and isolated. With different arrangements, this can form a tunnel lit from above, a chimney lit from the walls, or you can drape it over some scaffolding.

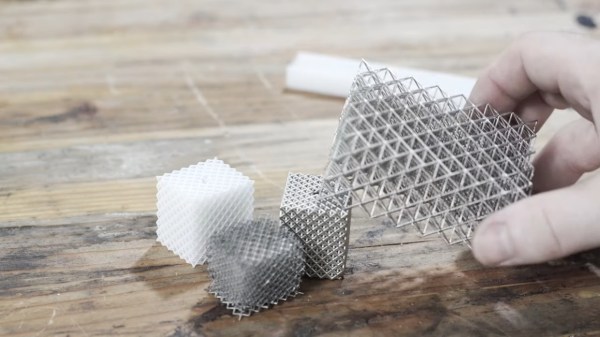

If you need something a little less portable for your own shop you might consider a mirror-filled chamber. One nice touch to add is a turntable to help make sure the entire part is cured without any missing areas.