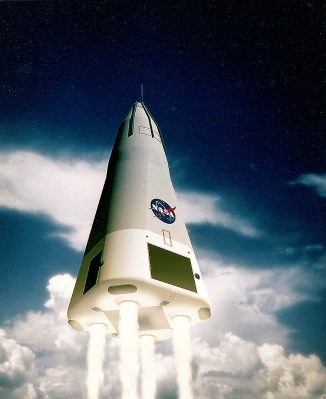

With all the talk of SpaceX and Blue Origin sending rockets to orbit and vertically landing part or all of them back on Earth for reuse you’d think that they were the first to try it. Nothing can be further from the truth. Back in the 1990s, a small team backed by McDonnell Douglas and the US government vertically launched and landed versions of a rocket called the Delta Clipper. It didn’t go to orbit but it did perform some extraordinary feats.

Origin Of The Delta Clipper

The Delta Clipper was an unmanned demonstrator launch vehicle flown from 1993 to 1996 for testing vertical takeoff and landing (VTOL) single-stage to orbit (SSTO) technology. For anyone who watched SpaceX testing VTOL with its Grasshopper vehicle in 2012/13, the Delta Clipper’s maneuvers would look very familiar.

The Delta Clipper was an unmanned demonstrator launch vehicle flown from 1993 to 1996 for testing vertical takeoff and landing (VTOL) single-stage to orbit (SSTO) technology. For anyone who watched SpaceX testing VTOL with its Grasshopper vehicle in 2012/13, the Delta Clipper’s maneuvers would look very familiar.

Initially, it was funded by the Strategic Defence Initiative Organization (SDIO). Many may remember SDI as “Star Wars”, the proposed defence system against ballistic missiles which had political traction during the 1980s up to the end of the Cold War.

Ultimately, the SDIO wanted a suborbital recoverable rocket capable of carrying a 3,000 lb payload to an altitude of 284 miles (457 km), which is around the altitude of the International Space Station. It also had to return with a soft landing to a precise location and be able to fly again in three to seven days. Part of the goal was to have a means of rapidly replacing military satellites should there be a national emergency.

The plan was to start with an “X” subscale vehicle which would demonstrate vertical takeoff and landing and do so again in three to seven days. A “Y” orbital prototype would follow that. In August 1991, McDonnell-Douglas won the contract for the “X” version and the possible future “Y” one. The following is the story of that vehicle and its amazing feats.

Continue reading “Delta Clipper: A 1990s Reusable Single-Stage To Orbit Spaceship Prototype”