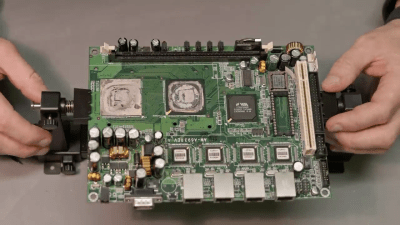

Moore’s law might not be as immutable as we once though thought it was, as chip makers struggle to fit more and more transistors on a given area of silicon. But over the past few decades it’s been surprisingly consistent, with a lot of knock-on effects. As computers get faster, everything else related to them gets faster as well, and the junk drawer tends to fill quickly with various computer peripherals and parts that might be working fine, but just can’t keep up the pace. [Bonsembiante] had an old ADSL router that was well obsolete as a result of these changing times, but instead of tossing it, he turned it into a guitar effects pedal.

The principle behind this build is that the router is essentially a Linux machine, complete with ALSA support. Of course this means flashing a custom firmware which is not the most straightforward task, but once the sound support was added to the device, it was able to interface with a USB sound card. An additional C++ program was created which handles the actual audio received from the guitar and sound card. For this demo, [Bonsembiante] programmed a ring buffer and feeds it back into the output to achieve an echo effect, but presumably any effect or a number of effects could be programmed.

For anyone looking for the source code for the signal processing that the router is now performing, it is listed on a separate GitHub page. If you don’t have this specific model of router laying around in your parts bin, though, there are much more readily-available Linux machines that can get this job done instead.