Names and labels are difficult. Take this “3D Printed” water-cooling loop by [Visual Thinker] on YouTube. It undeniably uses 3D printing — but it also uses silicone casting and laser-cut acrylic, too. All of these are essential parts, yet only 3D printing gets top billing in his thumbnail. At least the version we saw, anyway; the A/B testing game YouTubers play means that may change.

Perhaps that’s simply due to the contrast with [Visual Thinker]’s last build, where the “distro plate” that acts to plumb most of the coolant was made of layers of CNC-routed acrylic, held water-tight with O-rings. Not wanting to wait for his next build to be fabricated, and not wanting to take up CNC machining himself, [Visual Thinker] fell back on tools many of us have and know: the 3D printer and laser cutter.

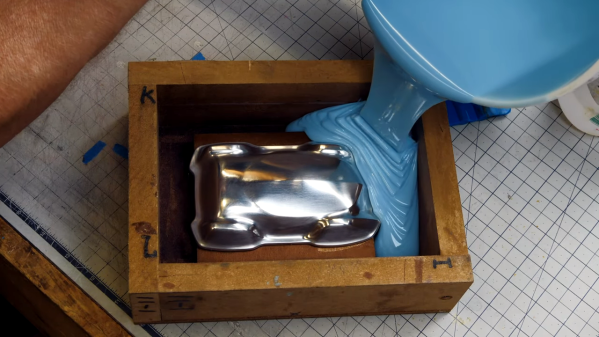

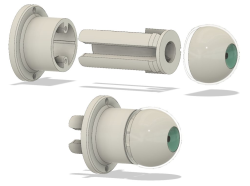

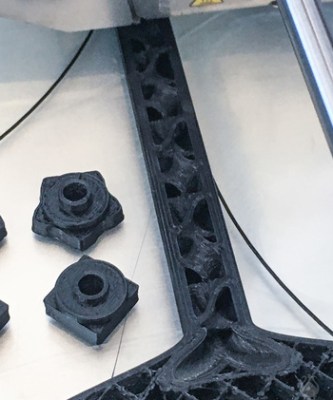

In this project, the end plates of the cooling loop are still clear acrylic, but he’s using a laser cutter to shape them. That means he cannot route out gaps for o-rings like in the last project, so that part gets 3D printed. Sort of. Not trusting the seal a 3D printed gasket would be able to give him, [Visual Thinker] opts to use his 3D printer to create a mold to cast a seal in silicone. Or perhaps “injection-mold” would be a better word than cast; he’s using a large syringe to force the degassed silicone into the mold. The end part is three pieces: a 3D printed spacer holding two acrylic plates, with the cast-silicone gasket keeping the whole thing water-tight to at least 50 psi, 10x the operating pressure of his PC.

After that success, he tries replacing the printed spacer with acrylic for a more transparent look. In that version only temporary shims that are used to form the mold are 3D printed at all, and the rest is acrylic. Even if you’re not building a water-cooled art PC, it’s still a great technique to keep in your back pocket for fluid channeling.

In some ways, this technique is the exact opposite of the copper-pipe steampunk builds we’ve featured previously. Those were all about pretty plumbing, while with a distro plate you hardly need pipes at all. Like any water-cooled project, it’ll need a radiator, which could be a hack in and of itself.

Continue reading “PC Watercooling Uses Everything But CNC Machining”

The parts [Jan] is making are interesting, as well. He observed that the process of swapping resin in his printer’s build tank was an unpleasant experience for a number of reasons, chief among them being that resin is sticky and messy, and the shape of the build tank doesn’t make pouring resin from it a clean job.

The parts [Jan] is making are interesting, as well. He observed that the process of swapping resin in his printer’s build tank was an unpleasant experience for a number of reasons, chief among them being that resin is sticky and messy, and the shape of the build tank doesn’t make pouring resin from it a clean job.