As the march of time continues on, it becomes harder and harder to play older video games on hardware. Part of this is because the original hardware itself wears out, but another major factor is that modern operating systems, software, and even modern hardware don’t maintain support for older technology indefinitely. This is why emulation is so popular, but purists that need original hardware often have to go to extremes to scratch their retro gaming itch. This project from [Eivind], for example, is a completely new x86 PC designed for the DOS and early Windows 98 era.

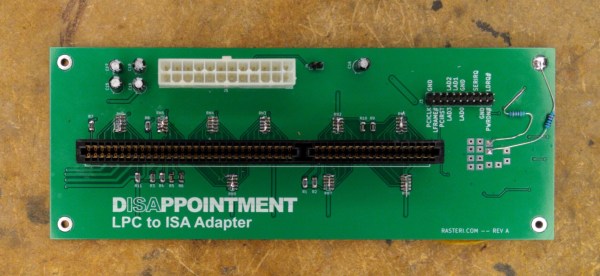

The main problem with running older games on modern hardware is the lack of an ISA bus, which is where the sound cards on PCs from this era were placed. This build uses a Vortex86EX system-on-module, which has a processor running a 32-bit x86 instruction set. Not only does this mean that software built for DOS can run natively on this chip, but it also has this elusive ISA capability. The motherboard uses a Crystal CS4237B chip connected to this bus which perfectly replicates a SoundBlaster card from this era. There are also expansion ports to add other sound cards, including ones with Yamaha OPL chips.

Not only does this build provide a native hardware environment for DOS-era gaming, but it also adds a lot of ports missing from modern machines as well including a serial port. Not everything needs to be original hardware, though; a virtual floppy drive and microSD card reader make it easy to interface minimally with modern computers and transfer files easily. This isn’t the only way to game on new, native hardware, though. Others have done similar things with new computers built for legacy industrial applications as well.

Thanks to [Stephen] for the tip!