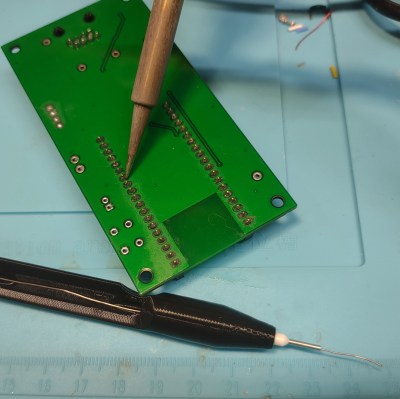

Soldering can get frustrating when you’re working fast. It often feels like you don’t have enough hands, particularly on jobs where you need to keep feeding solder in a hurry. To solve that issue, [mulcmu] developed a simple one-handed solder feeder.

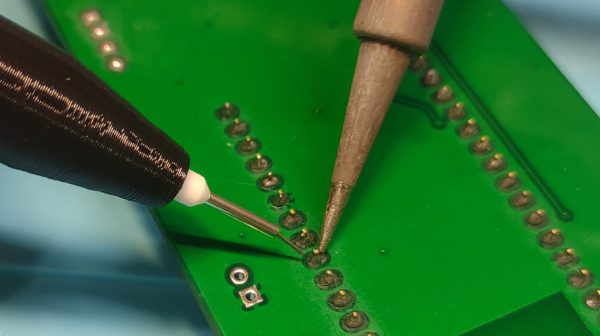

The intended use-case is for busy work like soldering long pin headers. The one-handed device allows solder to be continually fed while the other hand uses the soldering iron. It solves a long-running problem for [mulcmu], after their experiments with techniques inspired by TIG welding came to nought.

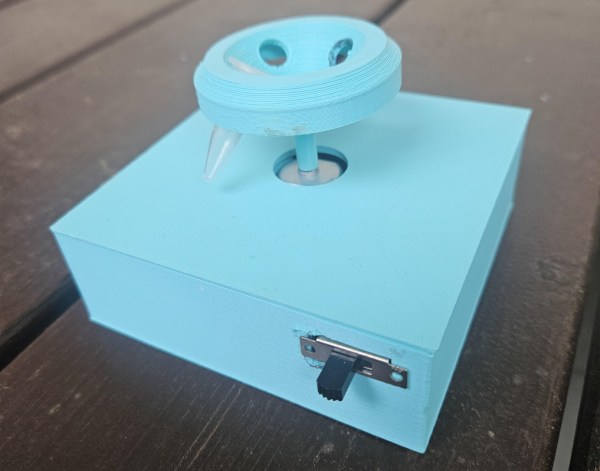

The design uses a pen-like form factor. A 3D-printed hollow tube has a wire ferrule inserted in the end, which serves as the tip of the device through which solder is fed. The tube has a cutaway, which allows the user to feed solder through using an easy motion of the thumb. The solder itself is fed from a spool in a regular bench top holder. If more slack is required in the solder feed, one simply pins the solder down in the device and tugs to draw more out.

If you find yourself regularly soldering repetitive jobs by hand, this could be a gamechanger for you. Those working in through-hole would be perhaps best served by this device. Meanwhile, if you’ve got nifty tool hacks of your own to share, don’t hesitate to let us know!