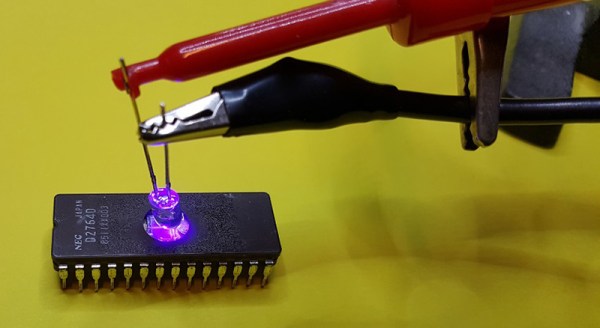

Editor’s Update: According to the schematic for this project, SST-10-UV-A130-F405-00 (PDF) LEDs are used which produce 405nm UV-A light. The manufacturer, Luminus, does not recommend that part for disinfection or sterilization. Luminus sells UV-C LEDs for that purpose, generating 275-285nm. After publication the part number used was changed to and American Opto L933-UV265-2-20 which is a UV-C LED producing 265-278nm.

The global COVID-19 pandemic has had a serious impact on the hacking and making scene, though it hasn’t been all bad. Sure, shipping on average is taking a lot longer than we’d like when ordering parts, but otherwise being stuck at home has given many people far more time to work on their projects than they would have had otherwise. In some cases, it’s also been a reminder of just how far we’ve come in terms of what the dedicated individual is capable of producing within the confines of their own home.

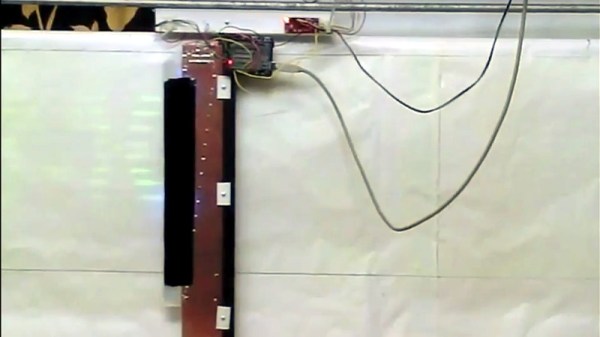

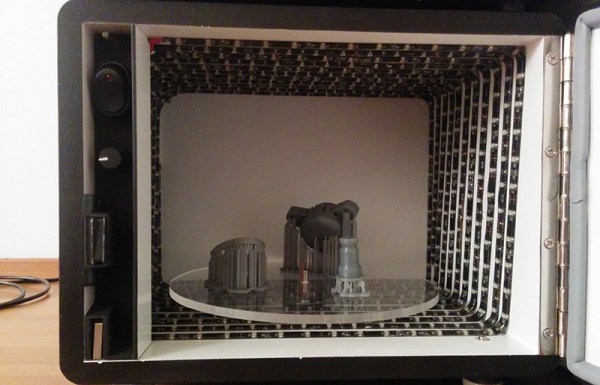

As a perfect example, take a look at this UV sanitizer box built by [Md Raz]. Looking for a way to quickly and easily kill germs on smartphones and other small devices, he used the considerable capabilities afforded to the modern hacker to produce a professional-looking device in far less time than it would have if he had to outsource things like PCB manufacturing or injection molding.

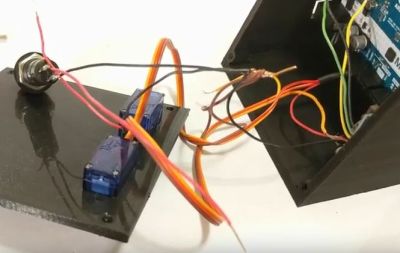

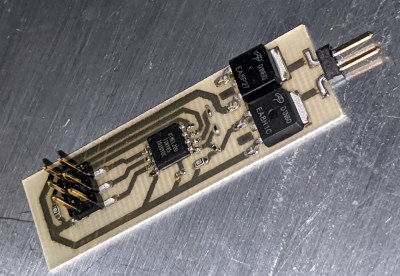

Inside the 3D printed enclosure is an array of SMD UV-C LEDs that, according to the manufacturer’s specs, will destroy viruses and bacteria in 5 minutes. To make sure the LEDs are given enough time to do their job, [Md] is using an ATtiny85 to control the countdown and a seven segment display to let the user know how much longer they have to wait. All the electronics are held on PCBs produced with a BotFactory SV2 desktop PCB printer, but for those of us with somewhat more limited budgets, a mill or even a modified laser engraver could be used to produce similar boards.

Inside the 3D printed enclosure is an array of SMD UV-C LEDs that, according to the manufacturer’s specs, will destroy viruses and bacteria in 5 minutes. To make sure the LEDs are given enough time to do their job, [Md] is using an ATtiny85 to control the countdown and a seven segment display to let the user know how much longer they have to wait. All the electronics are held on PCBs produced with a BotFactory SV2 desktop PCB printer, but for those of us with somewhat more limited budgets, a mill or even a modified laser engraver could be used to produce similar boards.

With everything going on, there’s understandably been increased demand for germicidal lights. But unfortunately, some unscrupulous manufacturers are trying to take advantage of the situation. Being able to select the LEDs for this device based on their specifications is arguably just as important as how quickly it was produced. Though we’d still advise a position of “trust, but verify” when it comes to UV-C.