Breathing LEDs are an attractive adornment on many electronic devices. These days they’re typically controlled by software but of course there were fading effects back in the days of analog too. [Pepijn de Vos] mixes a little of the new and the old by building a hardware-based fader from a Verilog design and even too the time to explain the process in depth.

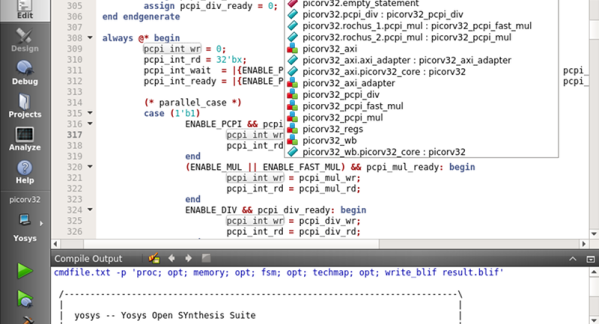

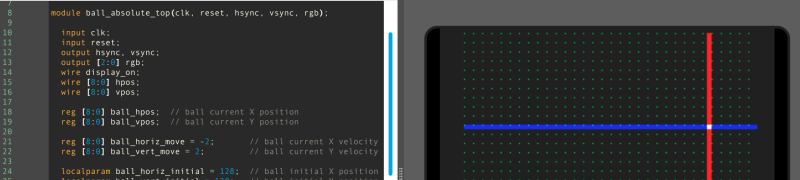

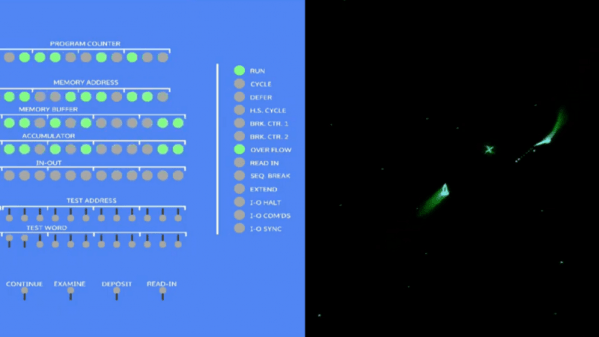

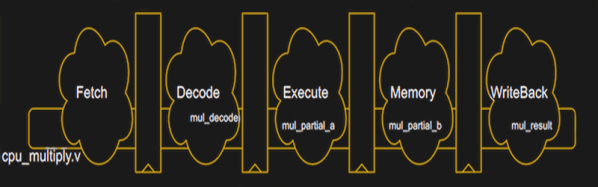

Rather than using a microcontroller and software, [Pepijn] wrote the logic required to make the LED “breathe” in the hardware description language, Verilog. You may be familiar with this for FPGAs, but using it to plan out a build with logic chips is just as apt a use. The Verilog was synthesized into a circuit using 74-series logic chips, with the help of work by [Dan Ravensloft] who has made a library for the Yosys Open Synthesis Suite. With the addition of a basic clock circuit, the LED is made to breathe and the rate can be controlled by changing the clock speed.

It’s a fun way to experiment with both Verilog and old-school logic, albeit one that may not scale well. An interesting side note from the Twitter thread, [Dan] estimates that with current settings the PicoRV32 CPU would require over 2000 chips to build. Regardless, it’s an interesting tool and one that likely has further scope for experimentation.

First patented by Apple way back in 2002, the breathing LED has been a popular project for those learning electronics. We’ve even seen it on motorbikes. Video after the break.

Continue reading “Breathing LED Done With Raw Logic Synthesized From A Verilog Design”