Aside from idle curiosity, very few of us need to see inside chips and components to diagnose a circuit. But reverse engineering is another story; being able to see what lies beneath the inscrutable epoxy blobs that protect the silicon within is a vital capability, one that might justify the expense involved in procuring an X-ray imager. But what’s to be done when such an exotic and expensive — not to mention potentially deadly — machine breaks down? Obviously, you fix it yourself!

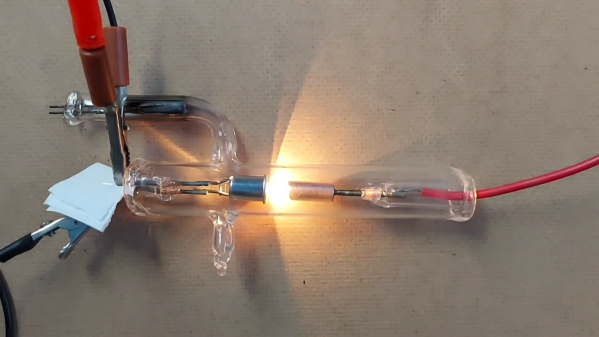

To be fair, [Shahriar]’s Faxitron MX-20 digital X-ray microscope was only a little wonky. It still generally worked, but just took a while to snap into the kind of sharp focus that he needs to really delve into the guts of a chip. This one problem was more than enough to justify tearing into the machine, but not without first reviewing the essentials of X-ray production — a subject that we’ve given a detailed look, too — to better understand the potential hazards of a DIY repair.

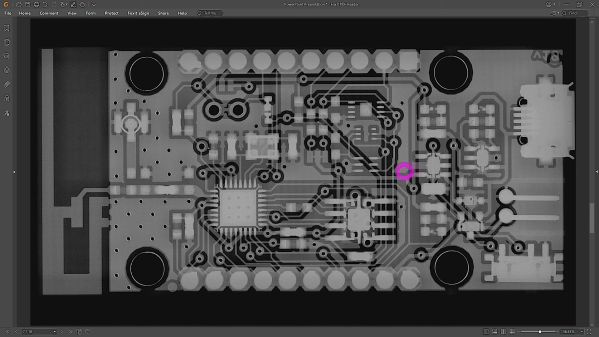

With that out of the way and with the machine completely powered down, [Shahriar] got down to the repair. The engineering of the instrument is pretty impressive, as it should be for something dealing with high voltage, heavy thermal loads, and ionizing radiation. The power supply board was an obvious place to start, since electrostatically focusing an X-ray beam depends on controlling the high voltage on the cathode cup. After confirming the high-voltage module was still working, [Shahriar] homed in on a potential culprit — a DIP reed relay.

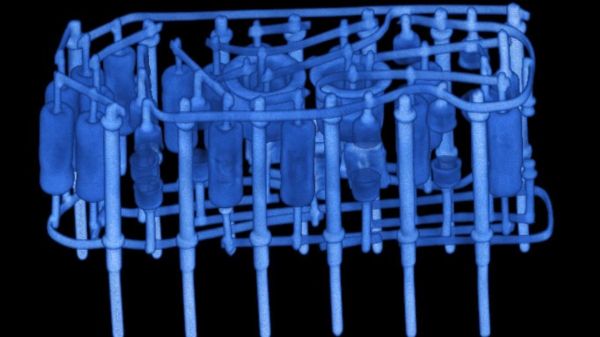

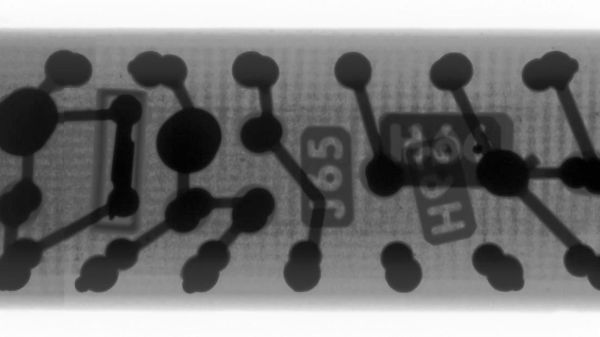

Replacing that did the trick, enough so that he was able to image the bad component with the X-ray imager. The images are amazing; you can clearly see the dual magnetic reed switches, and the focus is so sharp you can make out the wire of the coil. There are a couple of other X-ray treats, so make sure you check them out in the video below.

Continue reading “DIY Repair Brings An X-Ray Microscope Back Into Focus”

The trick here is having an X-ray sensing panel that can be reused. It takes around five seconds of exposure to grab each 40×40 cm frame which are then assembled back into video.

The trick here is having an X-ray sensing panel that can be reused. It takes around five seconds of exposure to grab each 40×40 cm frame which are then assembled back into video.