Open Science has been a long-standing ideal for many researchers and practitioners around the world. It advocates the open sharing of scientific research, data, processes, and tools and encourages open collaboration. While not without challenges, this mode of scientific research has the potential to change the entire course of science, allowing for more rigorous peer-review and large-scale scientific projects, accelerating progress, and enabling otherwise unimaginable discoveries.

As with any great idea, there are a number of obstacles to such a thing going mainstream. The biggest one is certainly the existing incentive system that lies at the foundation of the academic world. A limited number of opportunities, relentless competition, and pressure to “publish or perish” usually end up incentivizing exactly the opposite – keeping results closed and doing everything to gain a competitive edge. Still, against all odds, a number of successful Open Science projects are out there in the wild, making profound impacts on their respective fields. HapMap Project, OpenWorm, Sloan Digital Sky Survey and Polymath Project are just a few to name. And the whole movement is just getting started.

While some of these challenges are universal, when it comes to Biology and Biomedical Engineering, the road to Open Science is paved with problems that will go beyond crafting proper incentives for researchers and academic institutions.

It will require building hardware.

Continue reading “Open Hardware For Open Science – Interview With Charles Fracchia”

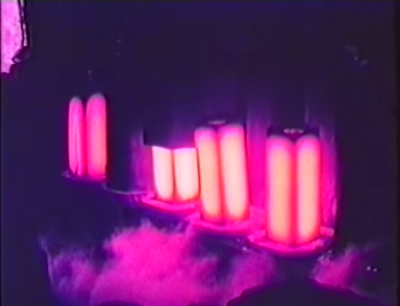

More importantly, [Bessemer]’s process resulted in steel that was ten times stronger than that made with the crucible-steel method. Basically, oxygen is blown through molten iron to burn out the impurities. The silicon and manganese burn first, adding more heat on top of what the oxygen brings. As the temperature rises to 1600°C, the converter gently rocks back and forth. From its mouth come showers of sparks and a flame that burns with an “eye-searing intensity”. Once the blow stage is complete, the steel is poured into ingot molds. The average ingot weighs four tons, although the largest mold holds six tons. The ingots are kept warm until they are made into rail.

More importantly, [Bessemer]’s process resulted in steel that was ten times stronger than that made with the crucible-steel method. Basically, oxygen is blown through molten iron to burn out the impurities. The silicon and manganese burn first, adding more heat on top of what the oxygen brings. As the temperature rises to 1600°C, the converter gently rocks back and forth. From its mouth come showers of sparks and a flame that burns with an “eye-searing intensity”. Once the blow stage is complete, the steel is poured into ingot molds. The average ingot weighs four tons, although the largest mold holds six tons. The ingots are kept warm until they are made into rail.