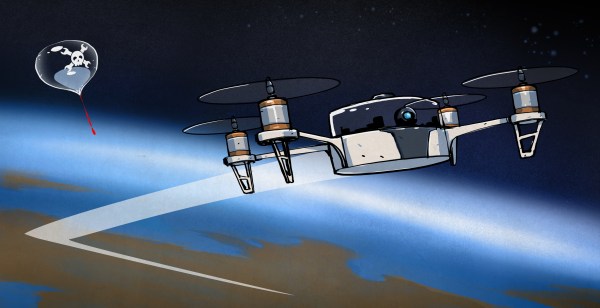

Your mission, should you choose to accept it, is to send a quadcopter to near space and return it safely to the Earth. Getting it there is not that difficult. In fact, you can get pretty much anything you want to near space with a high altitude weather balloon. Getting it back on the ground in one piece is a whole other ballgame.

Why does someone need to do this? Well, it appears the ESA’s StarTiger team is taking a card out of NASA’s book and wants to use a Sky Crane to soft land a rover on Mars. But instead of using rockets to hold the crane steady in the Martian sky, they want to use…you guessed it, a quadcopter. They’re calling it the Dropter.

At first glance, there seems to be a lot wrong with this approach. The atmosphere on Mars is about 100 times less dense than the Earth’s atmosphere at sea level. How do props operate in these conditions? Testing would need to be done of course, and the Earth’s upper atmosphere is the perfect place to carry out such testing. At 100,000 feet, the density of the stratosphere is about the same as that of the Martian surface atmosphere. AND 100,000 feet is prime high altitude balloon territory. Not to mention the gravity on Mars is about 38% of Earth’s gravity, meaning a 5.5 pound model on Earth could accurately represent a 15 pound model on Mars.

With all of these facts taken into consideration, one can conclude that realistic testing of a scale model Martian quadcopter is within the grasp of the hacker community. We’ve seen some work on high altitude drones before, but never a quadcopter.

Now it’s your turn to do something no one has ever done before. Think you got what it takes to pull such a project off? Let us know what your approach to the challenge would be in the comments.