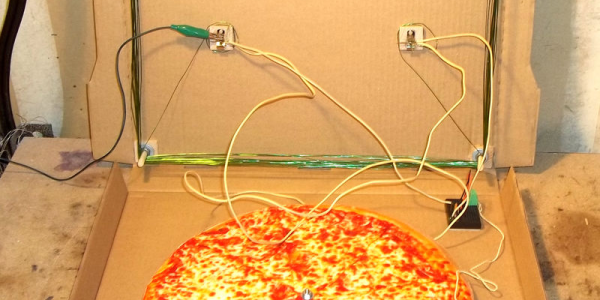

Sometimes you start building, and the project evolves. Layers upon layers of functionality accrue, accrete, and otherwise just pile up. Or at least we’re guessing that’s what happened with [Varun Kumar]’s sweet “Surveillance Car Controlled by DTMF“.

In case you haven’t ever dug into not-so-ancient telephony, Dual-tone, multi-frequency signalling is what made old touch-tone phones work. DTMF, as you’d guess, encodes data in audio by playing two pitches at once. Eight tones are mapped to sixteen numbers by using a matrix that looks not coincidentally like the old phone keypad (but with an extra column). One pitch corresponds to a column, and one to a row. Figure out which tones are playing, and you’ve decoded the signal.

Anyway, you can get DTMF decoder chips for pennies on eBay, and they make a great remote-control interface for a simple robot, which is presumably how [Varun] got started. And then he decided that he needed a cell phone on the robot to send back video over WiFi, and realized that he could also use the phone as a remote controller. So he downloaded a DTMF-tone-generator app to the phone, which he then controls over VNC. Details on GitHub.