If you’ve ever experienced the heartbreak of finding a seed in your supposedly seedless navel orange, you’ll be glad to hear that with a little work, you can protect yourself with an optical computed tomography scanner to peer inside that slice before popping it into your mouth.

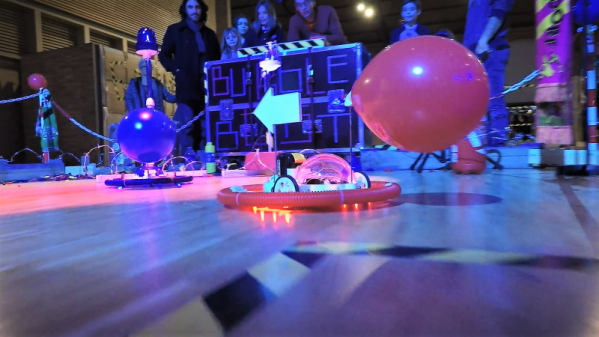

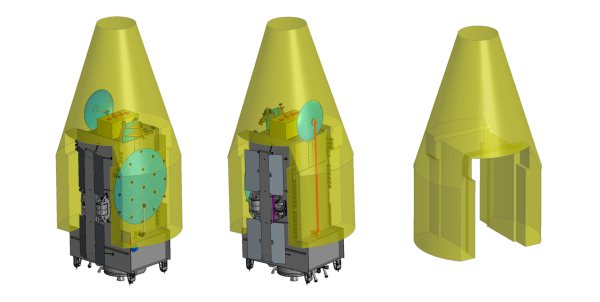

We have to admit to reading this one with a skeptical eye at first. It’s not that we doubt that a DIY CT scanner is possible; after all, we’ve seen examples at least a couple of times before. The prominent DSLR mounted to the scanning chamber betrays the use of visible light rather than X-rays in this scanner — but really, X-ray is just another wavelength of light. If you choose optically translucent test subjects, the principles are all the same. [Jbumstead]’s optical CT scanner is therefore limited to peeking inside things like slices of tomatoes or oranges to look at the internal structure, which it does with impressive resolution.

This scanner also has a decided advantage over X-ray CT scanners in that it can image the outside of an object in the visible spectrum, which makes it a handy 3D-scanner in addition to its use in diagnosing Gummi Bear diseases. In either transmissive or reflective mode, the DSLR is fitted with a telecentric lens and has its shutter synchronized to the stepper-driven specimen stage. Scan images are sent to Matlab for reconstruction of CT scans or to Photoscan for 3D scans.

The results are impressive, although it’s arguably more useful as a scanner. Looking to turn a 3D-scan into a 3D-print? Photogrammetry is where it’s at.

Continue reading “Visible Light CT Scanner Does Double Duty”

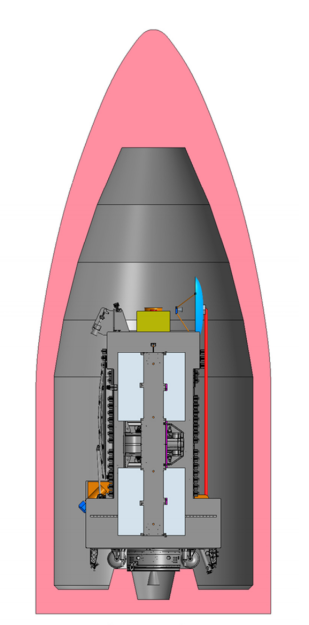

like a perfect excuse to dig through some juicy documentation, though unfortunately this may not be the bonanza of technical tidbits the Hackaday reader is looking for. Past the slick diagrams of typical satellites in rocket fairings, the three documents in question primarily provide broad guidance. There are notes about maximum power ratings, mass and volume guidelines, available orbits, and the like. Communication bus options are varied; there aren’t 1000BASE-T Ethernet drops but multiply redundant

like a perfect excuse to dig through some juicy documentation, though unfortunately this may not be the bonanza of technical tidbits the Hackaday reader is looking for. Past the slick diagrams of typical satellites in rocket fairings, the three documents in question primarily provide broad guidance. There are notes about maximum power ratings, mass and volume guidelines, available orbits, and the like. Communication bus options are varied; there aren’t 1000BASE-T Ethernet drops but multiply redundant