Wandering round the field at EMF Camp, our eye was caught by an unusual sight, at least to European eyes. The type of campervan body which sits on the back of a pickup truck is not particularly common on this side of the Atlantic, but there one was, fitted out as a mobile makerspace. If that wasn’t enough, this one is for sale.

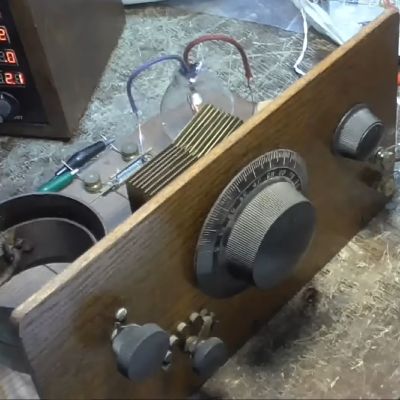

Here at Hackaday we’re neither estate agents or in the want-ads business, so we’re unaccustomed to property promotion. We’re still not immune to the attraction of a portable makerspace to take to events though, and this one provides a very practical basis. It started life as what Brits call a Luton van body, a box van, and inside it’s gained a small kitchen, benches and shelves either side, and up in the space over the cab, a double bed. Sadly the laser cutter and 3D printers aren’t included.

Here at Hackaday we’re neither estate agents or in the want-ads business, so we’re unaccustomed to property promotion. We’re still not immune to the attraction of a portable makerspace to take to events though, and this one provides a very practical basis. It started life as what Brits call a Luton van body, a box van, and inside it’s gained a small kitchen, benches and shelves either side, and up in the space over the cab, a double bed. Sadly the laser cutter and 3D printers aren’t included.

If you live in Southern England and you want to be the envy of everyone at your next hacker camp, an email to richjmaynard at gmail dot com with a sensible offer might secure it. We would be first in the queue if we had the space, because what Wrencher scribe wouldn’t want an office like this!