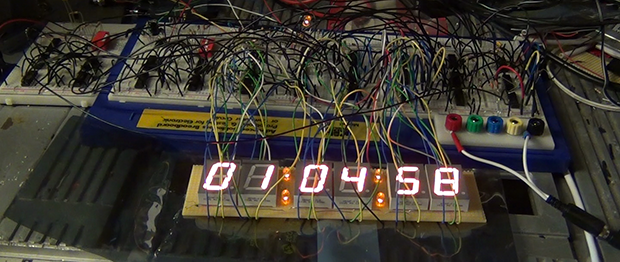

When a normal alarm clock just won’t do, the only option is to build your own, entirely out of discrete logic chips. [jvok] built this alarm clock for last year’s 7400 Logic Competition. In a desire to go against the grain a little bit, [jvok] decided to use 4000-series logic chips. It was allowed under the rules, and the result is a wonderful example of what can be done without a microcontroller.

Most clock projects we’ve seen use a single button to increase each digit. [jvok] wanted to do something unique, so he is able to set his clock with a ‘mode’ button that allows him to independently set the hours, minutes, and seconds. He’s only ever seen this method of setting a clock’s time used with microcontroller-based projects, and translating even that simple code into pure circuitry is quite impressive.

This clock also includes an alarm function, set by a bunch of DIP switches in binary coded decimal. It’s a great piece of work, and deserving of much more attention than it received during the Open Logic Competition.