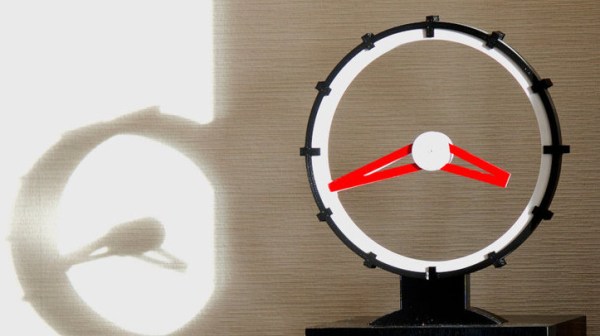

[Love Hultén]’s latest piece of interactive art is the SYNTH#BOI, a super-clean build with something of the semi-cyberdeck, semi-vintage computing vibe to it. The device is a combination synthesizer and visualizer, with a 15-inch display, MIDI keyboard, and based on an Intel NUC i5 small form factor PC.

There are not many details about the internal workings of the device, but the high quality of the build is very evident. Photos show a fantastic-looking enclosure with clean lines and sharp finish; it’s a reminder that careful measuring and attention to detail can be the difference between something that looks like a hack job, and something that looks like a finished product.

Watch the SYNTH#BOI in action in the video, embedded below. And if the name [Love Hultén] seems familiar, it’s probably because we featured his VOC-25 “Pink Denture Synth”, a concept instrument with a decidedly memorable design of its own.

Continue reading “Synth And Visualizer Combo Has Retrocomputing Vibe”

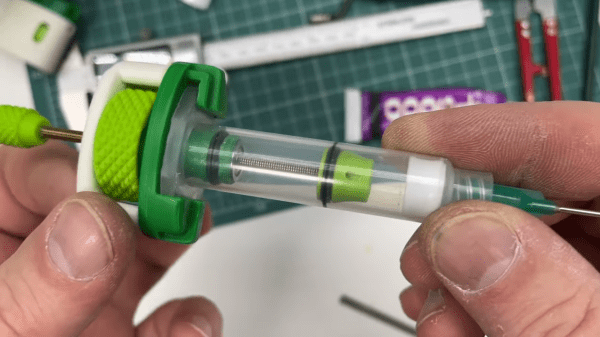

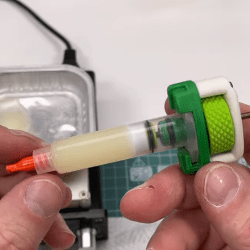

[Harry Gill] has you covered with

[Harry Gill] has you covered with

There is also a separate

There is also a separate