One of the sticking points for us with our own Internet of Things is, ironically, the Internet part. We build hardware happily, but when it comes time to code up web frontends to drive it all, the thrill is gone and the project is only half-done.

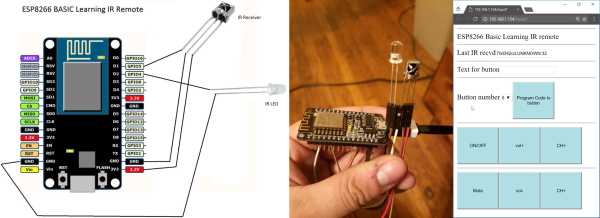

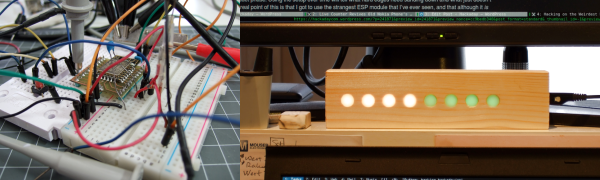

Including some simple web-based scripting functionality along with the microcontroller basics is one of the cleverest tricks up ESP8266 BASIC’s sleeves. BASIC author [mmiscool] puts it to good use in this short demo: a complete learning IR remote control that’s driven through a web interface, written in just a few lines of BASIC.

Note that everything happens inside the ESP8266 here, from hosting the web page to interpreting and then blinking back out the IR LED codes to control the remote. This is a sophisticated “hello world”, the bare minimum to get you started. The interface could look slicker and the IR remote could increase its range with more current to the LED, but that would involve adding a transistor and some resistors, doubling the parts count.

For something like $10 in parts, though, this is a fun introduction to the ESP and BASIC. Other examples are simpler, but we think that this project has an awesome/effort ratio that’s hard to beat.