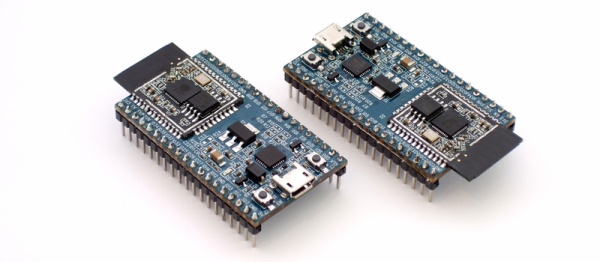

The ESP32 is looking like an amazing chip, not the least for its price point. It combines WiFi and Bluetooth wireless capabilities with two CPU cores and a decent hardware peripheral set. There were modules in the wild for just under seven US dollars before they sold out, and they’re not going to get more expensive over time. Given the crazy success that Espressif had with the ESP8266, expectations are high.

And although they were just formally released ten days ago, we’ve had a couple in our hands for just about that long. It’s good to know hackers in high places — Hackaday Superfriend [Sprite_tm] works at Espressif and managed to get us a few modules, and has been great about answering our questions.

We’ve read all of the public documentation that’s out there, and spent a week writing our own “hello world” examples to confirm that things are working as they should, and root out the bugs wherever things aren’t. There’s a lot to love about these chips, but there are also many unknowns on the firmware front which is changing day-to-day. Read on for the full review.

Enter the

Enter the