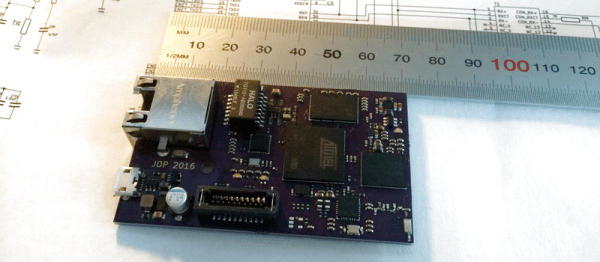

[KC Budd] wanted to make a car-tracking GPS unit, and he wanted it to be able to phone home. Adding in a GSM phone with a data plan would be too easy (and more expensive), so he opted for the hacker’s way: tunneling the data over DNS queries every time the device found an open WiFi hotspot. The result is a device that sends very little data, and sends it sporadically, but gets the messages out.

This system isn’t going to be reliable — you’re at the mercy of the open WiFi spots that are in the area. This certainly falls into an ethical grey zone, but there’s very little harm done. He’s sending a 16-byte payload, plus the DNS call overhead. It’s not like he’s downloading animated GIFs of cats playing keyboards or something. We’d be stoked to provide this service to even hundreds of devices per hour, for instance.

If you’re new here, the idea of tunneling data over DNS requests is as old as the hills, or older, and we’ve even covered this hack before in different clothes. But what [KC] adds to the mix is a one-stop code shop on his GitHub and a GPS application.

Why don’t we see this being applied more in your projects? Or are you all tunneling data over DNS and just won’t admit it in public? You can post anonymously in the comments!