When we first saw the Raspberry Pi Pico and its RP2040 microcontroller last month it was obvious that to be more than just yet another ARM chip it needed something special, and that appeared to be present in the form of its onboard PIO peripherals. We were eagerly awaiting how the community might use them to push the RP2040 capabilities beyond their advertised limits. Now [Luke Wren] provides us with an example, as he pushes an RP2040 to produce a DVI signal suitable to drive an HDMI monitor.

It shouldn’t be a surprise that the chip can be overclocked, however it’s impressive to find that it can reach the 252 MHz necessary to generate the DVI timing. With appropriate terminations it proved possible for the GPIO lines to mimic the differential signalling required by the spec. A PCB with the RP2040 and an HDMI socket was created, also providing a couple of PMOD connectors for expansion. All code and software can be found in a GitHub repository.

The result is a usable DVI output which though it is a relatively low resolution 640×480 pixels at 60 Hz is still a major advance over the usual composite video provided by microcontroller projects. With composite support on monitors becoming a legacy item it’s a welcome sight to see an accessible path to an HDMI or DVI output without using an FPGA.

Thanks [BaldPower] for the tip.

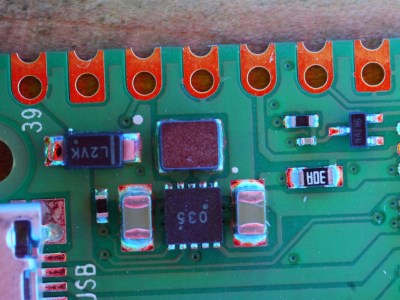

The principle behind this tool is as unexpected and simple as it is clever; by having different colours of light from different elevations of the dome it ensures that each different angle of the solder joint surface reflects a different colour. Thus a colour photograph shot from directly above the board allows visual inspection of the quality of the solder joints by the rainbow of colours that appears around their edges. This process can even be automated with OpenCV or similar, hence the process is referred to as Automated Optical Inspection, or AOI.

The principle behind this tool is as unexpected and simple as it is clever; by having different colours of light from different elevations of the dome it ensures that each different angle of the solder joint surface reflects a different colour. Thus a colour photograph shot from directly above the board allows visual inspection of the quality of the solder joints by the rainbow of colours that appears around their edges. This process can even be automated with OpenCV or similar, hence the process is referred to as Automated Optical Inspection, or AOI.