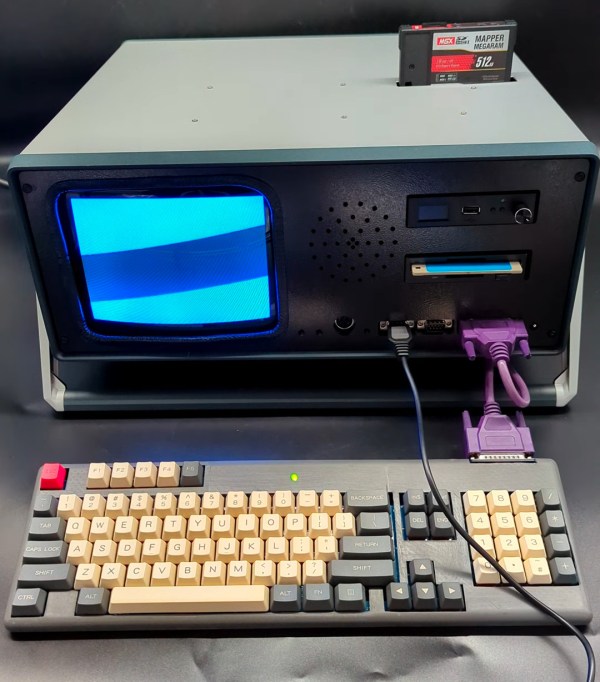

Something of a rarity in the US, the MSX computer standard was rather popular in other parts of the world but mostly existed in the computer-in-a-keyboard format popular in the 80s. [Aron Hoekstra aka “nullvalue”] wanted to build an MSX2 of their own, but decided to build it in a period-appropriate luggable form factor.

This build really tries to make the computer as plausibly vintage as possible including an actual CRT for the display instead of using an easier to obtain and package LCD. Computing is accomplished with an Omega Home Computer MSX2 SBC by [Sergey Kiselev] which uses components that could have been found when the MSX computers were in production. While 3D printing wasn’t widespread in the 80s, we can assume any of the plastic parts like the internal mounts would have been injection molded instead.

An impressive number of different techniques were used to bring this computer to life including PCB design, 3D printing, CNC, and plenty of soldering. After some troubleshooting on the 50 pin cartridge connector and all the assembly, [Hoekstra]’s Mega Omega MSX2 Portable Computer makes for a very impressive reimagining of the MSX platform that feels like a product that might have actually existed at the time.

If you want more MSX hacks, checkout how to add a Wii Nunchuck or PS2 or USB keyboards to your MSX.