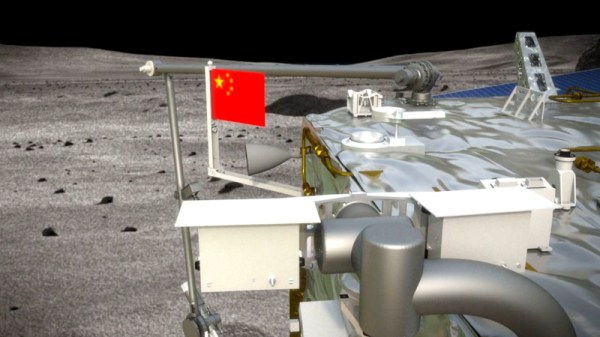

If everything goes according to plan, China will soon become the third country behind the United States and the Soviet Union to successfully return a sample of lunar material. Their Chang’e 5 mission, which was designed to collect 2 kilograms (4.4 pounds) of soil and rock from the Moon’s surface, has so far gone off without a hitch. Assuming the returning spacecraft successfully renters the Earth’s atmosphere and lands safely on December 16th, China will officially be inducted into a very exclusive club of Moon explorers.

Of course, spaceflight is exceedingly difficult and atmospheric reentry is particularly challenging. Anything could happen in the next few days, so it would be premature to celebrate the Chang’e 5 mission as a complete success. But even if ground controllers lose contact with the vehicle on its return to Earth, or it burns up in the atmosphere, China will come away from this mission with a wealth of valuable experience that will guide its lunar program for years to come.

In fact, one could argue that was always the real goal of the mission. While there’s plenty of scientific knowledge and not an inconsequential amount of national pride to be gained from bringing a few pounds of Moon rocks back to Earth, it’s no secret that China has greater aspirations when it comes to our nearest celestial neighbor. Starting with the launch of the Chang’e 1 in 2007, the Chinese Lunar Exploration Program has progressed through several operational phases, each more technically challenging than the last. Chang’e 5 represents the third phase of the plan, with only the establishment of robotic research station to go before the country says they’ll proceed with a crewed landing in the 2030s.

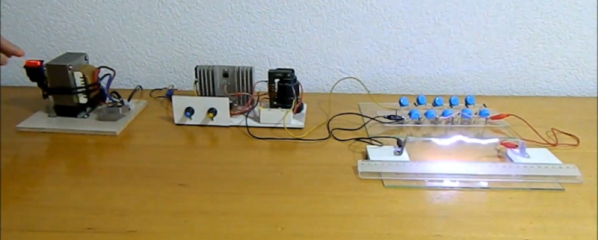

Which helps explain why, even for a sample return from the Moon, Chang’e 5 is such an extremely complex mission. A close look at the hardware and techniques involved shows a mission profile considerably more difficult than was strictly necessary. The logical conclusion is that China intentionally took the long way around so they could use it as a dry run for the more challenging missions that still lay ahead.

Continue reading “China’s Moon Mission Was About More Than Rocks”