[Ivan Miranda] is taking a very interesting approach to a marble clock. His design is a huge assembly that uses black and white marbles to create a (sort of) dot matrix display. It’s part kinetic art and part digital clock, all driven by marbles.

Here’s how it works: black and white marbles feed into a big elevator. This elevator lifts marbles to the top of the curved runs that make up the biggest part of the device. The horizontal area at the bottom is where the time is shown, with white and black marbles making up the numerical display. But how to make sure the white marbles and black marbles go in the right order?

The solution to that is simple. Marbles feed into the elevator in an unpredictable order. An array of sensors detects the color of each marble. Solenoids simply eject any marble that isn’t in the right place. For example, if the next marble for track n needs to be white, then simply kick out any black marbles in that position until there’s a white one. Simple, effective, and guarantees plenty of mesmerizing moving parts.

The solution to that is simple. Marbles feed into the elevator in an unpredictable order. An array of sensors detects the color of each marble. Solenoids simply eject any marble that isn’t in the right place. For example, if the next marble for track n needs to be white, then simply kick out any black marbles in that position until there’s a white one. Simple, effective, and guarantees plenty of mesmerizing moving parts.

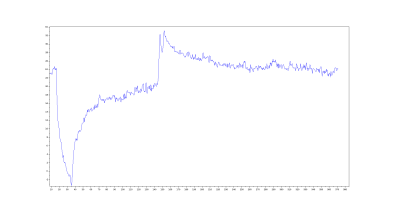

Of course, this means that marble ejection and marble color sensing need to be utterly reliable, and [Ivan] ran into problems with both. Marble ejection took some careful component testing and selection to get the right solenoids. Color sensing (as well as detecting empty spaces) settled on IR-based sensors commonly used in line-following robots.

You can watch the clock in action in the video embedded below just under the page break. We recommend giving it a look, because [Ivan] does a great job of showing all of the little challenges that reared their heads, and how he addressed them. There are still a few things to address, but he expects to have those licked by the next video. In the meantime, [Ivan] asks that if anyone knows a source for high quality glass marbles in bulk, please let him know. Low quality ones vary in size and tend to get stuck.

Marble clocks are great expressions of creativity, especially now that 3D printing is common. We love clock hacks, so if you ever create or run across a good one, let us know about it!

Continue reading “It’s A Marble Clock, But Not As We Know It” →