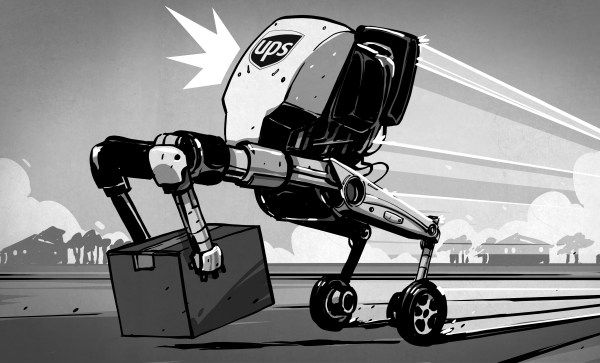

It should come as no surprise that we here at Hackaday are big boosters of autonomous systems like self-driving vehicles. That’s not to say we’re without a healthy degree of skepticism, and indeed, the whole point of the “Automate the Freight” series is that economic forces will create powerful incentives for companies to build out automated delivery systems before they can afford to capitalize on demand for self-driving passenger vehicles. There’s a path to the glorious day when you can (safely) nap on the way to work, but that path will be paved by shipping and logistics companies with far deeper pockets than the average commuter.

So it was with some interest that we saw a flurry of announcements in the popular press recently regarding automated deliveries. Each by itself wouldn’t be worthy of much attention; companies are always maneuvering to be seen as ahead of the curve on coming trends, and often show off glitzy, over-produced videos and well-crafted press releases as a low-effort way to position themselves as well as to test markets. But seeing three announcements at one time was unusual, and may point to a general feeling by manufacturers that automated deliveries are just around the corner. Plus, each story highlighted advancements in areas specifically covered by “Automate the Freight” articles, so it seemed like a perfect time to review them and perhaps toot our own horn a bit.

Continue reading “Automate The Freight: Autonomous Delivery Hits The Mainstream”