Twas the night before Christmas, and because I decided to make everyone’s presents myself this year, I’m still working like mad to get everything done before the big deadline. Why do I do this to myself? Well, partly because I enjoy the process.

My wife had this idea that we can make the older folks some fun decorative blinky things, and picked some motives. My son then drew them out on paper, and I scanned those drawings in and traced them over in CAD. We then cut the shapes out of wood on the CNC router, which turned out to be incredibly successful. (Now that I’ve done it, I wouldn’t be surprised if all of those “quirky” decorative objects that the Swedish flat-packers sell aren’t initially sketched out by third graders.)

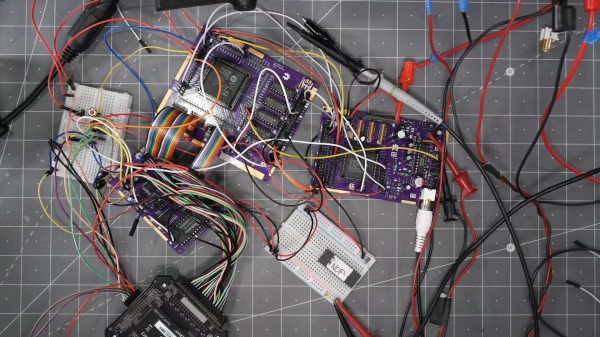

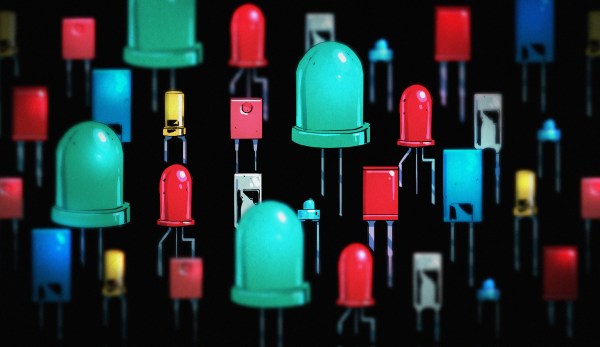

Then my son painted them, and it’s my job to insert the twinkling. I bought some of those three-wire “fairy lights” for the purpose, and they’re really fun to hack on. They’re like WS2812s, only instead of using four pins and shifting the data downstream, they’re on a bus, each with a hard-coded address – they know where they are in the string and each LED only listens for the Nth set of 24 bits. This means sending 200 color codes just to light up the 4 LEDs in Aunt Micki’s decorative tree, but so be it.

Last stop, and still to do as of the 23rd, route out some kind of wooden battery case, wedge in the LiPo and the charging circuits, and solder on an on/off switch. It’s down to the last minute, but isn’t that always the way?

Definitely would have been easier just to order something online. But is that the spirit of giving? No! The DIY way brings the family together, gets me some quality time with the CNC machine, and tones up my FreeCAD skills. My son even looked over my shoulder as we were coding some of the LED animations. And nothing says Christmas like hand-coded blinkies.

Happy Holidays, y’all!

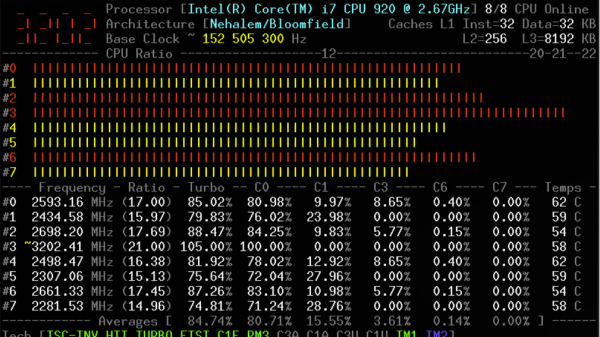

The tool relies on a kernel module, and is coded primarily in C, with some assembly code used to measure performance as accurately as possible. It’s capable of reporting everything from core frequencies to details on hyper-threading and turbo boost operation. Other performance reports include information on instructions per cycle or instructions per second, and of course, all the thermal monitoring data you could ask for. It all runs in the terminal, which helps keep overheads low.

The tool relies on a kernel module, and is coded primarily in C, with some assembly code used to measure performance as accurately as possible. It’s capable of reporting everything from core frequencies to details on hyper-threading and turbo boost operation. Other performance reports include information on instructions per cycle or instructions per second, and of course, all the thermal monitoring data you could ask for. It all runs in the terminal, which helps keep overheads low.