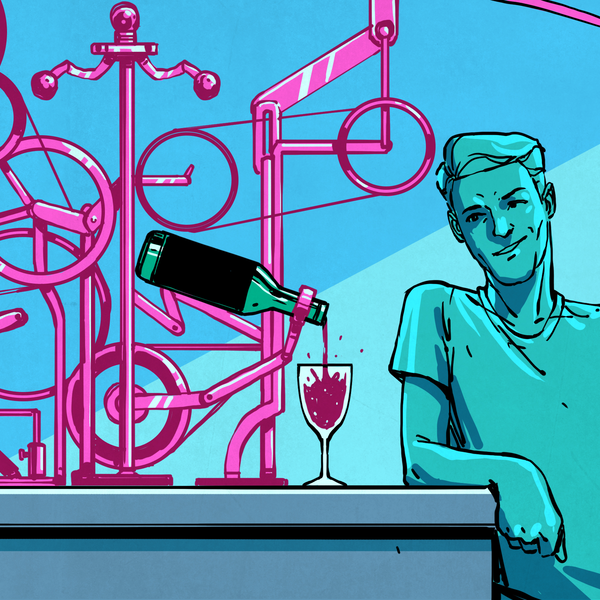

The festive season is often as good a reason as any to get out the tools and whip up a fun little project. [Simon] wanted a little tchotchke to give out for the holidays, so they whipped up a Christmas tree PCB that’s actually Arduino-compatible.

It’s a forward-looking project, complete with USB-C connector, future-proofing it for some time until yet another connector standard comes along. When plugged in, like many similar projects, it blinks some APA102 LEDs in a festive way. The PCB joins in on the fun, with white silkscreen baubles augmented by golden ones created by gaps in the soldermask.

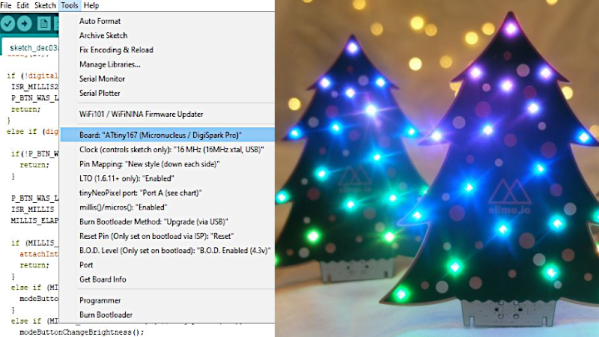

An ATTiny167 is the brains of the operation, using the Micronucleus bootloader in a similar configuration to the DigiSpark Pro development board. It relies on a bit-banged low-speed USB interface for programming, but the functionality is largely transparent to the end user. It can readily be programmed from within the Arduino IDE.

It’s not an advanced project by any means, but is a cute giveaway piece which can make a good impression in much the same way as a fancy PCB business card. It could also serve as an easy tool for introducing new makers to working with addressable LEDs. Meanwhile, if you’ve been cooking up your own holiday projects in the lab, don’t hesitate to drop us a line!