Rarely a week goes by that some company doesn’t offer to send us their latest and greatest laser. You know the type — couple of aluminum extrusions, Class 4 diode flopping around in the breeze, and no enclosure to speak of unless you count the cardboard box they shipped it in. In other words, an accident waiting to happen. Such gracious invitations get sent to the trash without a second thought.

Now don’t get me wrong, I have no doubt that the average Hackaday reader would be able to render such a contraption (relatively) safe for use around the shop. Build a box around it, bolt on a powerful enough fan to suck the smoke out through the window, and you’ve turned a liability into a legitimate tool. But the fact remains that we simply can’t put our stamp on something that is designed with such a blatant disregard for basic safety principles.

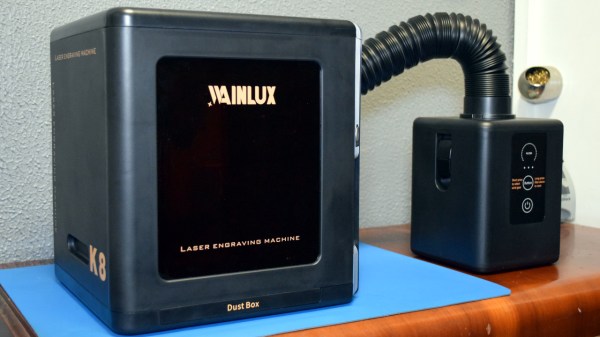

That being the case, a recent email from WAINLUX nearly met the same fate as all those other invitations. But even at a glance it was clear that this new machine they wanted to send out, the K8, was very different from others we’d seen. Different even from what the company themselves have put out to this point. This model was fully enclosed, had a built-in ventilation fan, an optional air filter “sidecar”, and yes, it would even turn off the laser if you opened the door while it was in operation. After reading through the promotional material they sent over, I had to admit, I was intrigued.

It seemed like I wasn’t the only one either; it was only a matter of days before the Kickstarter for the WAINLUX K8 rocketed to six figures. At the time of this writing, the total raised stands at just under $230,000 USD. There’s clearly a demand for this sort of desktop laser, the simplicity of using a diode over a laser tube is already appealing, but one that you could actually use in a home with kids or pets would be a game changer for many people.

But would the reality live up to the hype? I’ve spent the last couple of weeks putting a pre-production WAINLUX K8 through its paces, so let’s take a look and see if WAINLUX has a winner on their hands.

Continue reading “Review: WAINLUX K8, A Diode Laser That’s Ready To Work”

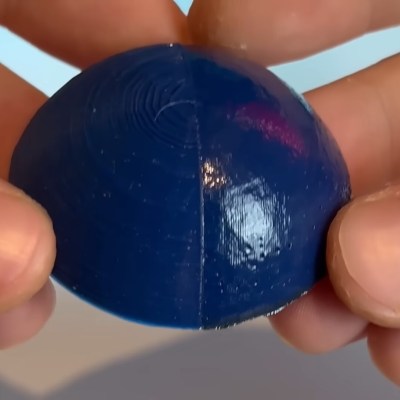

The smoothing process begins at the end of a 3D print and uses non-planar printer movements to keep the laser at an ideal focusing distance. The results proved rather effective, giving a noticeably smoother and shiner quality than an unprocessed print. The smoothing works incredibly well on fine geometry which would be difficult or impossible to smooth out via traditional mechanical means. Some detail was lost with sharp corners getting rounded, but not nearly as much as [TenTech] feared.

The smoothing process begins at the end of a 3D print and uses non-planar printer movements to keep the laser at an ideal focusing distance. The results proved rather effective, giving a noticeably smoother and shiner quality than an unprocessed print. The smoothing works incredibly well on fine geometry which would be difficult or impossible to smooth out via traditional mechanical means. Some detail was lost with sharp corners getting rounded, but not nearly as much as [TenTech] feared.