Wikipedia says “The uncanny valley hypothesis predicts that an entity appearing almost human will risk eliciting cold, eerie feelings in viewers.” And yes, we have to admit that as incredible as it is, seeing [Automaton Robotics]’ hand and forearm move in almost human fashion is a bit on the disturbing side. Don’t just take our word for it, let yourself be fascinated and weirded out by the video below the break.

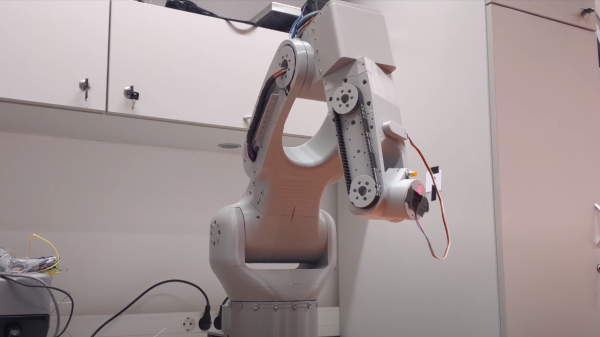

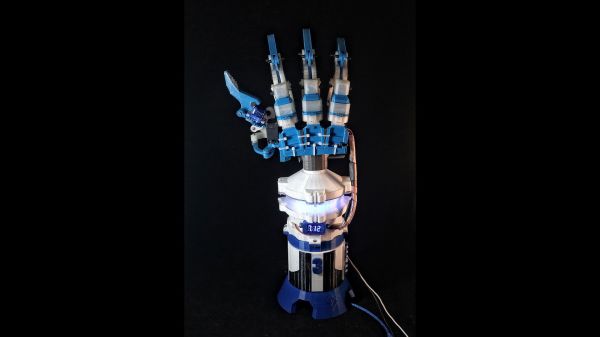

While the creators of the Artificial Muscles Robotic Arm are fairly quiet about how it works, perusing through the [Automaton Robotics] YouTube Channel does shed some light on the matter. The arm and hand’s motion is made possible by artificial muscles which themselves are brought to life by water pressurized to 130 PSI (9 bar). The muscles themselves appear to be a watertight fiber weave, but these details are not provided. Bladders inside a flexible steel mesh, like finger traps?

[Automaton Robotics]’ aim is to eventually create a humanoid robot using their artificial muscle technology. The demonstration shown is very impressive, as the hand has the strength to lift a 7 kg (15.6 lb) dumbbell even though some of its strongest artificial muscles have not yet been installed.

A few years ago we ran a piece on Artificial Muscles which mentions pneumatic artificial muscles that contract when air pressure is applied, and it appears that [Automaton Robotics] has employed the same method with water instead. What are your thoughts? Please let us know in the comments below. Also, thanks to [The Kilted Swede] for this great tip! Be sure to send in your own tips, too!

Continue reading “Taking A Stroll Down Uncanny Valley With The Artificial Muscle Robotic Arm”