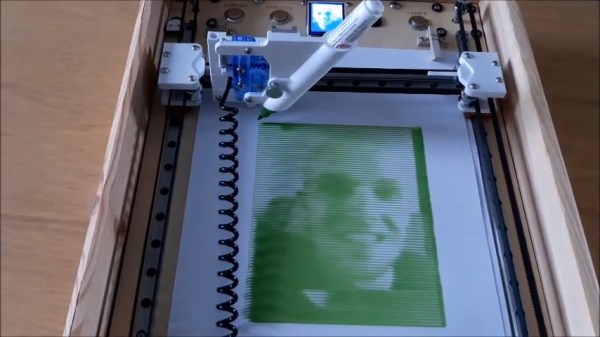

Ornithopters look silly. They look like something that shouldn’t work. An airplane with no propeller and wings that go flappy-flappy? No way that thing is going to fly. There are, however, a multitude of hobbyists, researchers, and birds who would heartily disagree with that sentiment, because ornithopters do fly. And they are almost mesmerizing to watch when they do it, which is just one reason we love [Hobi Cerdas]’s build of the Pterothopter, a rubber band-powered ornithopter modeled after a pterodactyl.

All joking aside, the science and research behind ornithopters and, relatedly, how living organisms fly is fascinating in itself — which is why [Lewin Day] wrote that article about how bees manage to become airborne. We can lose hours reading about this stuff and watching videos of prototypes. While most models we can currently build are not as efficient as their propeller-powered counterparts, the potential of evolutionarily-perfected flying mechanisms is endlessly intriguing. That alone is enough to fuel builds like this for years to come.

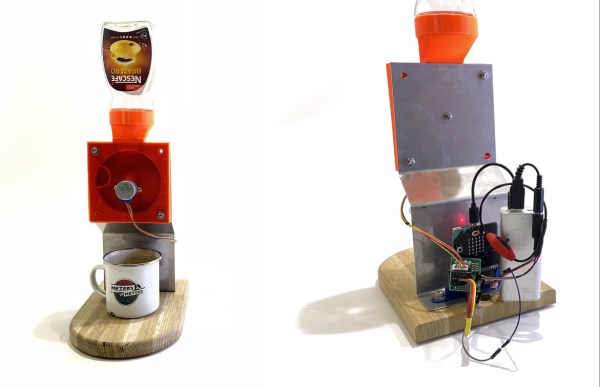

As you can see in the video below, [Hobi Cerdas] went through his own research and development process as he got his Pterothopter to soar. The model proved too nose-heavy in its maiden flight, but that’s nothing a little raising of the tail section and a quick field decapitation couldn’t resolve. After a more successful second flight, he swapped in a thinner rubber band and modified the wing’s leading edge for more thrust. This allowed the tiny balsa dinosaur to really take off, flying long enough to have some very close encounters with buildings and trees.

For those of you already itching to build your own Pterothopter, the plans come from the Summer 2017 issue of Flapping Wings, the official newsletter of the Ornithopter Society (an organization we’re so happy to learn about today). You can also find more in-depth ornithopter build logs to help you get started. And, honestly, there’s no reason to limit yourself to uncontrolled flight; we’ve come across some very impressive RC ornithopters in the past.

Continue reading “Flight Of The Pterothopter: A Jurassic-Inspired Ornithopter”